*Note: In this 2013 interview, Tsitsi Dangarembga discusses a book called Chronicle of an Indomitable Daughter which was later published as This Mournable Body, shortlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize.

In 1988, at the age of twenty-eight, Tsitsi Dangarembga published her first novel, Nervous Conditions. Immediately acclaimed by Alice Walker and Doris Lessing, the book has come to be considered one of Africa’s most important novels of the twentieth century. Lessing wrote: “This is the novel we have all been waiting for . . . it will become a classic.” Set in Rhodesia in the 1960s, almost twenty years before Zimbabwe won independence and ended white minority rule, the novel’s heroine, Tambudzai Sigauke, embarks on her education. On her shoulders rest the economic hopes of her parents, siblings, and extended family, and within her burns the desire for “personhood,” to no longer be part of such an “undistinguished humanity.” Nervous Conditions borrows its title from Jean-Paul Sartre’s introduction to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, in which Sartre evokes the “disassociated self” created by colonialism: “Our enemy betrays his brothers and becomes our accomplice; his brothers do the same thing. The status of ‘native’ is a nervous condition introduced and maintained by the settler among colonized people with their consent.”

Nervous Conditions was the first book in what would become a trilogy. However, eighteen years would pass before Dangarembga published her second novel, The Book of Not. With its searing observations, devastating exploration of the state of “not being,” wicked humour, and astonishing immersion into the mind of a young woman growing up and growing old before her time, the novel is a masterpiece. Dangarembga is almost alone in mining the psychological “nervous condition” in African women and the relationship between this troubled inner landscape and the current crisis in contemporary Zimbabwe. In the last decades, she has chosen film as her medium and founded the International Images Film Festival for Women in Zimbabwe, which is now in its twelfth year. In 2006, the Independent named Dangarembga one of the fifty greatest artists shaping the African continent. Last year, she completed the final book, Chronicle of an Indomitable Daughter, which will be published in Zimbabwe in 2013.

I first met Tsitsi Dangarembga in Nigeria in 2010, where we taught a workshop organized by Helon Habila. Habila had never met Dangarembga before, but he told me that his experience of reading Nervous Conditions decades ago had marked and changed him. When I met Tsitsi, Zimbabwe was moving forward from a disastrous 2008 election that saw the opposition Movement for Democratic Change pull out of the second round of the presidential vote in the wake of widespread and horrific violence. At the same time, the economy had collapsed: between 2007 and 2008, the rate of inflation was seven sextillion percent. As much of the world knows, a power-sharing agreement was reached between Robert Mugabe and Morgan Tsvangirai in 2008, and Zimbabwe retreated from the news headlines. In the fall of 2012, Tsitsi invited me to come and teach in Harare. She envisioned a workshop called Breaking the Silence, which would gather testimonies from across Zimbabwe on political and domestic violence. These testimonies, which could be submitted anonymously, would form the basis of our reading material. Any Zimbabwean interested in writing could come into the workshop, read the collected testimonies, and, informed by these stories (more than one hundred were collected), write fiction. Tsitsi asked these writers to think not only about the victims but also about the lives and histories of the perpetrators. She also asked each of us to consider our own acts of violence or aggression, including instances when we used our authority or status for purposes of intimidation or personal gain. She wanted writers to claim these stories, wrestle with and interrogate them, and, finally, bring them back to the communities from which they came. As someone from outside, I did not know if what Tsitsi imagined was possible; I must admit, I was stunned and moved to find that it was.

We had this conversation in early December 2012, on the balcony of Tsitsi’s home in Harare, at sunset, just before I caught my flight home.

Thien: I wanted to ask you about the few years you spent overseas in the 1960s, when you were a child. Outside of Rhodesia and white minority rule, what was it like?

Dangarembga: In England?

Thien: Yes. I’m wondering about your first experience of race.

Dangarembga: The racism in England was not so institutionalized. Well, it was institutionalized, but then it was so efficiently realized that it didn’t need institutions, if you understand what I mean. In England, it was much easier not to be affected by it to that extent because my parents were students and people were somewhat respectful.

Thien: And you were six when you returned to Rhodesia.

Dangarembga: Coming back here . . . you know, it was such a shock. Everywhere we’d been before, my parents were so well respected. But in Rhodesia, the fact that we were black meant that once we walked into that society, all of that meant nothing. It was really a blow.

You might actually say that white people in this part of the world were so insecure, I suppose about having so many black people around, that they had to make their institutions into very obvious apartheid structures. But the whole internalized attitude, that’s been going on for centuries, these are attitudes that we have.

It was very interesting for me to have a character like Tambudzai, who understands the lack of respect because of poverty but not because of blackness. When she is taken into her uncle’s house, she feels everything is now okay because the poverty factor is no longer effective. Then she moves into the school [the elite Young Ladies’ College of the Sacred Heart, a convent school attended by mostly white students], where she’s doing everything as well as everyone else. The only issue is her blackness. She has an experience, a different kind of movement, into that position. Because if you have always been aware of racism, I think that you develop ways of dealing with it. I think it was Ama Ata Aidoo who said she didn’t even know there was such a thing as racism until she came to Germany. That’s where she learned she was black. So it was a bit the same for Tambudzai. She knew she was poor, and she knew she was uneducated because she could see the poverty of her home and she could see the differences with her relatives who were educated. But then she had to learn that she was black.

Thien: Yet Nervous Conditions begins as a very hopeful book. Does this hope come because she sees her freedom in relatively straightforward terms, that education will equal emancipation?

Dangarembga: Tambudzai starts off as a typical gifted child. She achieves a lot through her own initiative, and she sees the world as an arena in which she can act and succeed, no matter what comes. In a childish way, she thinks of herself as a kind of superwoman, but she cannot succeed on those terms because there never has been such a person, there has never been a superman or a superwoman. Sometimes what one perceives as freedom binds you more tightly.

There was so much invested during the Rhodesian era in educating Africans only up to a certain level and for certain tasks. An illusion had to be created, however, that there was some sort of mobility and fairness in the system. People like Tambudzai were swept up in that illusion. She had to find her own painful way out of it.

Thien: At the beginning, she also looks for freedom through selfhood, and the concept of unhu. The traditional greeting is “How are you?” “I am well if you are well too.” Can you describe unhu?

Dangarembga: This is a very interesting concept. In South Africa, ubuntu is exactly the same kind of philosophy, which is “I am because you are” or “I am because we are.” This is the kind of philosophy that used to bind villages and communities together until other forces interrupted those communities. So now I feel that this idea of “I am because you are”—meaning there is no great difference between you and me, so if you need something I can give it to you because I know you’re just like me, and when I need it you will also give it to me—has been disconnected from its material, physical base because of the way the world has progressed. Yet people retain the psychological emotion of it. So here we have a whole nation of Zimbabweans thinking we’re so wonderful because we have this unhu. We believe in “I am because we are,” and certainly, symbolically, we know that’s part of our framework and our reference, but on the ground it’s not happening anymore because all the conditions have changed and do not support that notion. And so this is why there is so much questioning in that book. Is this really the unhu that I believe in, that I came from? People are not behaving in that way anymore. Tambudzai does not resolve it for herself, but I think that there is a kind of a metanarrative there that shows the complexities, that actually the society has moved away from unhu even if they think they haven’t.

Thien: I was fascinated by the idea that personhood, or wholeness, requires reciprocity. But unhu was completely incompatible with the Rhodesian political structure, wasn’t it?

Dangarembga: Absolutely, I would say so. But I would not only say that it’s not reciprocated. For sure, when you come out of the confines of a society that had unhu, you kind of expect to find it elsewhere, which was baffling to Tambudzai in the beginning. But also, once you’ve gone outside and you’ve come back, the question is, do you also experience that from your own people? Or will they now see you as somebody outside the whole unhu construct? I feel that she has become an outsider, especially with her mother. You know, the mother should have been really happy for her daughter, and then that relation would have been reciprocal. But then Tambudzai is denied the comforts of home, and the mother is also denied the benefits of associating with a daughter who has some education and some access to the exterior world. Even if the construct doesn’t transfer outside, does it persist when the person comes back? If not, then the person coming back also becomes part of the fragmentation, as we see in the third book.

Thien: In the end, the pragmatic ones who accept the status quo, which is white rule, seem to flourish. Halfway through the trilogy, Tambu has refused to accept society as it is, and she nearly loses herself. Why?

Dangarembga: When I write, I try not to put messages in but to say, Are we here or are we there? You’ll find people who are willing to accept what happens at the advertising agency, thinking, Well okay, the money I’m getting is better than sweeping floors somewhere. So they protect their position. And then there are the type of people who will talk about it at parties or when they’re with their friends and just shake their heads and laugh. But can that be said to be emancipation? It’s this internalization of your own inferiority that Tambudzai has to struggle against. The question becomes, Do you identify with the sector of society that has money and business opportunities? That’s what people aspired to before. Or do you identify with other women like yourself? Where do you place yourself?

I realize that creative women often do not fit easily into certain paradigms. I think to myself, Then where do they go? Where do they go? Because I feel that these women have so much to contribute, that they just see things in a different way. Every society has people like that and marginalizes them in some way. So it’s a very difficult situation.

Thien: Can I detour here and ask how you left medicine? You were at Cambridge and you came home and went in an entirely different direction.

Dangarembga: I’d been studying psychology at the University of Zimbabwe, and I became involved in the drama club there and did a couple films. I started writing seriously, plays and prose, and I just felt that was really my niche. I was studying industrial psychology at the time I was seriously writing, but I realized it was going to be a struggle to make a living out of writing. So I thought, Okay, what other things can I do that are still within narrative and dealing with powerful subjects and putting ideas out there? I began to see the usefulness of film in a country like Zimbabwe. We boast about an 80 percent literacy rate. But even if you’re literate, which means you can fill in a form, it doesn’t mean you can read a piece of literature and understand what’s going on. So it seemed to me that film was also a very important medium for telling the stories that I felt needed to be told.

Thien: But why turn to film at the moment when you had such enormous international success with Nervous Conditions?

Dangarembga: Oh, Nervous Conditions was not so successful in the beginning. I finished it in 1984 and tried to have it published here, but most of the publishing houses at that time had young black men who had been outside the country writing and then came back and became the editors. When I submitted Nervous Conditions they would never give it respect. I realized they would never engage with a voice like mine.

Thien: Really?

Dangarembga: Yes, it took me four years.

Thien: So it was published outside first, in 1988?

Dangarembga: Yes, the Women’s Press. I actually didn’t know it was going to be published. So I thought, Let me try to do something different.

Thien: Were you already in film school in Berlin?

Dangarembga: I’d applied and been accepted. So when I got that letter I thought, I’m not going to lose this chance. I’m going to take it. Then what happened is that there was this huge conflict between the amount of work I was doing in film and in prose. But I just had to do the work together.

Thien: What was the conflict?

Dangarembga: They were just completely different. The skills I had learned for prose didn’t work in film. Those telling details, they’re completely different. Or the fact of these inner monologues in which you can write a whole book. Whereas prose is teasing out, film is stripping down, concentrating and compacting. I found I could not learn the one while doing the other. So it was a big struggle, actually. It took me years.

Thien: So The Book of Not was put aside.

Dangarembga: Yes, because I found I couldn’t do the two. Now that I feel I’m proficient in both, it seems to be working. But at the time, I really felt that I could not write The Book of Not while I was learning how to speak in film language.

Thien: Seventeen years, though! How could you keep Tambudzai quiet?

Dangarembga: Oh, my goodness! She was hopping mad. But you know, the point is, about the war and the racism, Nervous Conditions ends just as the war intensifies, 1977. So it was a very difficult thing to want to allow Tambudzai to talk. Because what she had to say is what happens in The Book of Not, and it wasn’t something that I thought at that time would be useful. I thought that with the kinds of divisions we had, it might be more inflammatory than anything else. The war might have brought us a little nearer to where we think we want to be as a people, but what did it consist of? It consisted of lies, forced abductions, horrible brutality on both sides, and treachery even within families. Afterwards it was just, Let’s forget, that’s all behind us. We had slogans like “This is the year of the people’s transformation.” I was young. I believed it.

So I think it was actually quite good for me to have something else to do at the time. It was only when other conflicts began again at the end of the 1990s that I thought, Tambu has this story to tell that is actually appropriate for what’s happening.

Thien: In what way was it appropriate?

Dangarembga: Because at the end of the 1990s, the whole land issue came up in Zimbabwe. We were looking at about 80 percent of the land being owned by about 20 percent of the population, which brought back the issues of racism, imbalance, and inequality. Zimbabwe had simply pretended 1890 to 1980 hadn’t happened, and many people had gone on with the same prejudices as before. It all came up again. And that’s exactly what Tambudzai was experiencing after Nervous Conditions. What resurfaced in the 1990s was in accordance with what she went through. And so, at that time when the villagers were assembling and organizing themselves into battalions that were going out into farms, I felt it was appropriate to look at those issues of race and who owns what and who has the power to bequeath what to whom in a fairly innocuous story of a young girl at school. You know, a kind of, “If you have ears to hear, then you will hear.”

Thien: Tambudzai has so much anger but not against the system itself. It all goes inward. Do you think it’s her own personhood that disturbs her most?

Dangarembga: You know, this idea of the happy African is something I really wanted to interrogate. Because if someone smiles at you it does not mean they’re happy. It just means “I think that if I smile I might get out of this alive!” And so I wanted to look into this notion of the happy African. Who is this person you are saying is the happy African? Is this person really happy? And if this person is not happy, then what is likely to be happening in this person’s life? Is this smiling, this being so complicit with the system, going to benefit society in the long run? And, of course, from my perspective as the writer, I thought not. But it was also important for me not to write an obvious kind of situation where black people are angry with white people because that doesn’t get us anywhere either. It was much more important for me to try to show to people what is happening to individuals within a certain system, and to hope that, after hearing this, people will understand, and maybe their conscience will become a little more open to things they were not open to before.

Thien: Christopher Okigbo talked about an inner exile in his generation of educated Nigerians, that they were so fully assimilated into Englishness that their ethnic memory was erased. Would it be fair to say that Tambudzai’s education expands, but also erases, her sense of self?

Dangarembga: That is true, but I think this is a reflection of what happens in almost anyone’s life. We all have our dreams. We dream about happiness and security and how to achieve them. Sometimes we do not achieve what we dreamt of and find we can be wonderfully happy without it, or with something else. Other times we do obtain what we dreamt of and find that it has not given us the peace and contentment we wished for. It is all about coming to terms with the conditions. The big problem for Tambudzai is that Rhodesian society is asking her to come to terms with a system that negates her as an African woman, and the sad thing is that she does not, cannot, or will not see that the system has nothing but contempt for her. So she tries to adjust until she becomes contemptible herself. I don’t know how she makes it through, but she does.

Thien: What about Nyasha? She’s about the same age as Tambudzai, but she looks at things directly. It’s the silence of everyone around her that breaks her down.

Dangarembga: That’s why Nyasha just goes away. Then she can consolidate herself, and when she’s ready, she comes back. I was so shocked, though, because about five or six years after Nervous Conditions was published, I asked some young women what they thought happened to Nyasha, and they said they thought she died.

Thien: I did too. Dangarembga: Oh, really? Thien: I feared she would die. I’ll never forget the scene where Babamukuru finally realizes he has to get help for Nyasha. The psychiatrist in Umtali says that Nyasha can’t be ill because “Africans did not suffer in the way we had described.”

Dangarembga: These days it’s not so difficult to go out of the country and find somewhere else where you can just explore who you are. It was important for me to say, “Whoever you are, whatever your fight is, you can come through.” I have friends who committed suicide, and I think that was actually my task, to bring these two young women through so that people can see that it’s possible, it doesn’t matter, there is a way forward. Look, the mother comes through also. All the women come through. I think the one who comes through least is Nyasha’s mother.

Thien: She’s the most educated, the one who has achieved the most, and she just disappears.

Dangarembga: Yes, she just disappears. I think the difference for Nyasha’s mother is that she doesn’t know what the conflict is. Because she has this wonderful social situation by virtue of marrying Babamukuru . . . Is she going to leave him? Whereas for the other female characters the adversity is much more concrete. It’s easier for them to grapple with it.

Thien: By the beginning of the third book, Tambu’s sense of self is severely fragmented. But the novels themselves are not fragmented. I’d say they are actually very classical. The thread never breaks. The storytelling never falters, not for a moment. Was this conscious? How did you approach it?

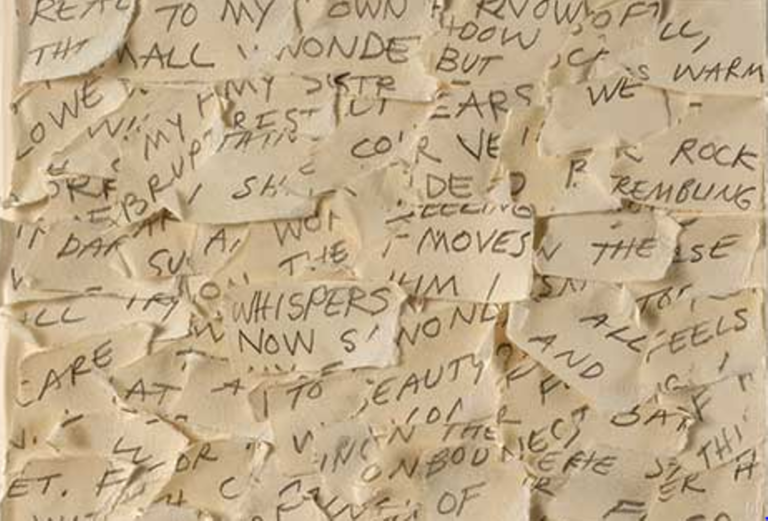

Dangarembga: Thanks, Maddie. I struggled to get that continuity. I struggled hard. That’s why everything took so much longer than I thought. And when it got too much, I had to have the courage to leave it until I was ready to go back. It was being alert at any moment so that if a phrase came I could write it down to contemplate later. It was very much like inviting the work to join me and waiting until it decided it would.

Thien: I had the chance to see some of your writing process these past few weeks. You get so deeply inside the psychology. You become the mindset. Was this a skill you had from the beginning, even before the writing?

Dangarembga: It is something I picked up early because I had to understand for myself why people were the way they were, and I had to be able to cope with the understanding I got. For me, the way to understand a character is motivation, so I have to focus on that. Once I understand why a character is behaving a certain way, everything else, all the other attributes, fall into place.

Thien: And then how do you step back? Is there a point of too much understanding?

Dangarembga: Stepping back is sometimes more painful than going in. A writer once said to me, “I thought I was writing it out, but actually I’m writing it in!” Also there were places I did not want to go with Tambudzai. The way she hates other black people was traumatic for me. The extent of her violence was disturbing. Her return to the village breaks my heart. But I still think, Let’s have it out in the open, then perhaps we can move on.

Thien: By the third book, white rule is finished, Zimbabwe is a new country, but the war has gone inside. Tambudzai breaks down, but just before this happens we hear what she tells her student: “You say if they do not want an A-level in biology then they will get an A-level in violence.”

Dangarembga: Is that what she says? She says it to her student?

Thien: In Chronicle . . .

Dangarembga: As I said, I started writing the second book during the land invasions at the end of the 1990s, and violence had reappeared as a way of life in Zimbabwe. I knew there must be an issue with violence here that we were not addressing. And also this idea of “we happy Africans are smiling at you” does not mean that we are free of violence. Actually, Tambudzai was a very appropriate character for me to explore what is happening underneath that happy African surface. There is all . . . all this rage that maybe the people themselves do not know is rage. But it comes out from time to time. And it definitely was an issue for me to say to people, Look, we tell the world that we are peace-loving, but are we really? When at the drop of a hat teachers can beat people to the extent where they lose eyes or they even die. There are stories like this. So it was important for me to say, The war is behind us, but if we have now incorporated this kind of violence into the very fabric of our society, are we aware of it? Are we concerned about it? To say, I am concerned, as the writer, as Tsitsi. To say, Let’s really look at ourselves.

But I think this is why these books are very difficult. They’re difficult for everyone because if you are not a black Zimbabwean, you don’t want to have to identify with some of the characters. I was on a reading tour for The Book of Not and a young woman came up and said, “I really want to apologize. My mother was at school with you. I hope she wasn’t one of those people.” People do not know it. It’s astonishing, but they really do not.

So I think it was difficult for people to read The Book of Not, and it will be really difficult for them to read Chronicle because I’m asking people to make certain connections. I do think we also need the kind of narrative that questions and helps you take a few steps further than you have been. That was also the basic idea in the workshop, Breaking the Silence. All these stories of violence: Are we just accepting them? Are we not making the connections because it’s easier? What is there to do about it? And for me, that’s why it was so emotional at the end of the workshop. I was beginning to despair of finding Zimbabweans who understood where I was coming from. It’s always, oh, you know, You’re out on a limb again! You’re causing discomfort! You’re disrupting and making everyone so uncomfortable! So it was really a special moment for me to have those eight people, besides yourself and myself, in that room. And to really feel we were all understanding the significance, the necessity. It was one of the most gratifying experiences I’ve ever had in my life.

Thien: Nobody walked away. This surprised me.

Dangarembga: I hope that they’ll be able to take it further. I’m not going to take it further. I think I’ve done my thing. If somebody ever contacts me and says, Can you . . . ? But you know, it also takes its toll on me. [Tsitsi is taking the project further, and has continued to mentor the writers who participated. She will be publishing the stories from the workshop in late 2013.]

Thien: When I look around me in Harare, there are entire interactions I wouldn’t know how to begin describing. And I realize I can’t find the words because I don’t actually know what I’m seeing. There’s a complex system of silences that you also have to find the language for.

Dangarembga: Yes. Mmm. You know, the language is really important. If I want to say certain things in Shona to a Shona speaker, I don’t have the language. First, because Shona is basically pre-colonial, so that whole experience of being colonized and being warped toward yourself is not really something we have put into language yet. Then the other language is English, whose purpose, I suppose, is to be imperial. You know, I’ve often looked in dictionaries to see if there is a word for people who enslave other people. You’d expect there’d be a word like enslavers or something. There isn’t. Or the dictionaries I’ve looked in haven’t got it! So English hasn’t got the language either.

The language in Shona is for the collective “you.” Shona is also very passive, as I think you might have noticed, and the language of narrative has to be active so it pushes the narrative along. I think that’s what I see as my job. So, okay, if this is what is now necessary to put into language, into narrative, how can I do it? It is a great act of magic to make submission active.

Thien: Can you read an excerpt from The Book of Not to give an example of Tambudzai’s submission?

Dangarembga: Sure.

Could I conceive of standing up and looking around me in a different manner? I could not. Truly, I could not imagine that I should have looked around me in another way, and analyzed what was taking place from my own perspective. For to do that, one requires a point of view . . . I resorted to the usual way of not feeling anything, of concentrating on every inch of skin, on the opening of every pore until I could feel nothing else and the sensation of me filled the entire universe. But I was not, I could feel nothing, and when I had come to this point of not being, I took the precaution of appropriately looking down.

Thien: Did you have mentors? Dangarembga: I was very fortunate to come into my writing career in the 1980s, when Toni Morrison was coming onto the scene. And also Alice Walker. I think that, now, the book of Alice Walker’s that I prefer most is Meridian, about this young woman coming of age in her late teens, early twenties, during the civil rights movement. She knows that she’s got to keep walking. But as a human being and as a woman you don’t want to always be nurturing conflict, as it were.

And I remember very specifically there was this point where the protagonist is crying. Tears stream down her face as she works. I was a young woman in my mid-twenties when I read it then; it didn’t speak to me. Now I don’t have access to a copy, but I remember that scene after more than three decades. So I had good role models. You know, Toni Morrison is absolutely fearless. I’m actually very fearful, so, you know, it takes a lot out of me to pretend I’m fearless.

Thien: That’s why you have “indomitable” in the title of the third book!

Dangarembga: Exactly! Just to convince myself. But yes, to have been coming into my writing career at a time when African American women were also making their mark and during this wonderful flowering of the literature, that was very good for me.

What I did notice however, especially with Toni Morrison, is that if you’re African American you have slavery as a construct around which to frame your narrative. Everyone has a view that slavery was evil and that it was a crime against humanity. It’s very different when you’re dealing with something that people have not generally accepted as having been criminal, such as colonization. This different set of values makes it very difficult for me to engage with the atrocities in my work without appearing pugnacious. And then, it sounds foolish, but another example comes from the biblical teaching that you take everything unto yourself. So Tambudzai had to become the essence of all that is wrong in order to get people to come along with her and see what’s wrong. That for me is the only way it will work, by making the person represent both sides of the story, as it were. I can’t confront people all the time. If I do that I begin to become my own worst nightmare.

Thien: Would you say Tambudzai was fortunate to go mad? It forced her to see that all is not well.

Dangarembga: Exactly. It was her own conscience that was telling her somewhere that this is not right. Which is why she couldn’t sustain it.

It was extremely intricate and extremely taxing to take all that violence into myself. But you have to live in your world otherwise it doesn’t ring true, it doesn’t resonate. But I’m glad it’s done now.

Thien: How do you know it’s done? Dangarembga: Oh, I know! It’s definitely finished. I know what happens to the characters and, you know, I could write it but it wouldn’t be anything new. It would just be, okay, everything went happily and then—

Thien: I just feel so attached to her.

Dangarembga: I don’t think I would be adding another dimension to our understanding of the way things work in Zimbabwe. So I don’t need to.

Thien: Do you see young Zimbabwean writers coming up now really confronting society the way that you do or that Dambudzo Marechera did?

Dangarembga: To be honest, I’m a little concerned about the status of writing here in Zimbabwe. The political situation is so prominent, it allows people not to deal with the real human side of the conflicts. In other words, it’s very easy to say, This person is from that party, the Dictator’s Party, and this person is from the good party, the Party of One Who Is Going to Free Us from the Dictatorship, and to frame it in those terms.

Also, we don’t really have publishers of fiction. The flip side of that is, if you put your manuscript together, you can publish yourself. And the way that you publish is that you get development aid money, which is really not concerned with quality. It’s just concerned with empowering people to do things. So they can also empower people to put certain narratives into the marketplace. And I think there’s a lot of this going on.

I think we are going through a phase where we are not pushing our writers to give of their highest. So I think that we are not being fair to them. Our experience in the workshop showed us that when people come in with something that has potential, when they just need that guidance to get closer, they will do it. One of the things I really want to do is start working on a new institution where creative arts, narrative, and performance can be taught properly. If we could only nurture properly, Zimbabwe could be really significant, not only in literature but also in music, dance, everything. But we’re just not harnessing that. We are not enabling our young people to realize their potential. And that’s something I want to change. Which is also why I’m mentoring these young women. This is on a very small scale, we have three or four in the office all the time, but it’s something.

Thien: They’re making films. They’re publishing.

Dangarembga: Yes, I hope we get there. There is an idea in Zimbabwe that is very prevalent. People think, I am, therefore I can. I think it would be more useful to think, Because I am, I can learn. However, to learn is to imply that someone has a capacity you do not. That does not sound egalitarian. And it suggests that you are somehow less, somehow inferior to the other person, and this brings back a lot of ghosts concerning inferiority. As a result, few people want to be told how things might be better done. So for me, it was mind-blowing in the workshop to see how Ignatius [Mabasa, a Zimbabwean novelist and poet who works in Shona and co-taught the workshop with us] could suggest to a writer, “How about this?” “How about that?” And to have them take it in. Underneath all the superficiality, people are craving that guidance. They must be. And they must be conscious that the society is not giving it to them either. So I wouldn’t like to make any blanket statements about the young people who are writing now, but I really feel that we, who should be setting things up for them, are really doing them a disservice.

Thien: You were away for a little while in the late 1990s. Was it difficult to come home?

Dangarembga: No, I had gone abroad specifically to acquire skills, which I did. It was not a difficult decision. I always knew I was coming back. It was simply a question of when.

Thien: What do you find most striking when you go back to Nervous Conditions after all these years?

Dangarembga: The agility of the narrative and the joy and hope in the text.

Thien: Thanks, Tsitsi.

Dangarembga: Thank you, Maddie.

brickmag