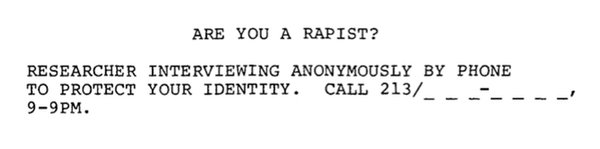

In 1976, a Ph.D. candidate at Claremont Graduate University placed a rather unusual personal ad in newspapers throughout Los Angeles:

He sat by his phone, sceptical that it would ring. “I didn’t think that anyone would want to respond,” said Samuel D. Smithyman, now 72 and a clinical psychologist in South Carolina.

But the phone did ring. Nearly 200 times.

At the other end of the line were a computer programmer who had raped his “sort of girlfriend,” a painter who had raped his acquaintance’s wife, and a school custodian who described 10 to 15 rapes as a means of getting even with “rich bastards” in Beverly Hills.

By the end of the summer, Dr. Smithyman had completed 50 interviews, which became the foundation for his dissertation: “The Undetected Rapist.” What was particularly surprising to him was how normal these men sounded and how diverse their backgrounds were. He concluded that few generalizations could be made.

Over the past few weeks, women across the world have recounted tales of harassment and sexual assault by posting anecdotes to social media with the hashtag #MeToo. Even just focusing on the second category, the biographies of the accused are so varied that they seem to support Dr. Smithyman’s observation.

But more recent research suggests that there are some commonalities. In the decades since his paper, scientists have been gradually filling out a picture of men who commit sexual assaults.

The most pronounced similarities have little to do with the traditional demographic categories, like race, class and marital status. Rather, other kinds of patterns have emerged: these men begin early, studies find. They may associate with others who also commit sexual violence. They usually deny that they have raped women even as they admit to nonconsensual sex.

This may be partly connected to a tendency to consider sexual assault a women’s issue even though men usually commit the crime. But finding the right subjects also has complicated the research.

Clarifying these and other patterns, many researchers say, is the most realistic path toward curtailing behaviors that cause so much pain.

“If you don’t really understand perpetrators, you’re never going to understand sexual violence,” said Sherry Hamby, editor of the journal Psychology of Violence. That may seem obvious, but she said she receives “10 papers on victims” for every one on perpetrators.