Frank Wills expected another boring and tedious night.

The twenty-four-year-old security guard was making his normal rounds on June 17, 1972. He was usually alone in the office building during his overnight shift. His routine consisted of checking each door in the large complex. The building was considered so safe, Wills only carried a can of mace for personal defense.

He came on duty at midnight and carried out his first check of the offices, starting in the basement and working methodically up to the 11th floor. It was tedious work, trying the handle of each office door to confirm it was properly secured.

It was also a sticky night and, when he had finished his first round, Wills went for an orange juice at the Howard Johnson motel across the road. As he passed by a basement door in the parking garage, he noticed a piece of tape covering the latch. He did not consider this unusual at the time, and removed the gaffer’s tape.

“A lot of times we’d have engineers doing work late at night. They’d place something in the door because they’d be coming right back so I really didn’t pay much attention to it.”

When he came back, he saw the door taped again, making him immediately suspicious. It was time to report a possible burglary.

“I just got to thinking,” said Wills, “there’s somebody in this building besides me.” So he rushed up to the lobby telephone, called for the services of the Second Precinct Police. Nothing big,” recalled Wills. “That’s the instructions. With just a can of mace, I couldn’t confront a burglar who might have a gun.”

D.C. Metro police officers John Barrett and Paul Leeper arrived in minutes. Wills showed them the door with tape still covering the latch. On their way up to the sixth floor, Wills was notified about another tenant that needed to leave the building. He left to go help.

The officers continued on, and discovered yet more tape on a latch, leading to a sixth floor office. They burst into the room, guns drawn. When Leeper and Barrett shouted for the suspects to put their hands in the air, 10 hands went up — the officers in plainclothes were facing a group of burglars in business suits.

“McCord said to me twice, he said, ‘Are you the police?’ And I thought, ‘Why is he asking such a silly question? Of course we’re the police,’” Leeper said. “I don’t think I’ve ever locked up another burglar that was dressed in a suit and tie and was in middle age.”

Five men were arrested. Bernard L. Barker, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, James McCord Jr., and Frank Sturgis were caught with “bugging devices, tear gas pens, many, many rolls of film, locksmith tools, and thousands of dollars in hundred dollar bills consecutively ordered.”

The men were linked to a nefarious group operating as fixers for President Richard Nixon: “The White House Plumbers.” The office they were sent to wiretap, the Democratic National Committee, was the target of Nixon’s reelection campaign. This was the first chain in a series of events that ended with the historic resignation of the president. Nixon, haughty and paranoid, believed that anything was on the table to guarantee him a win in the 1972 election.

Nixon paid a price for his arrogance. For all the meticulous planning of the White House Plumbers, they were foiled by an observant night watchman at the Watergate office complex.

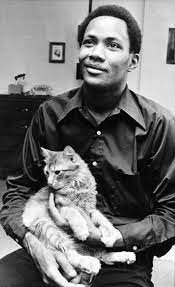

Frank Wills was an immediate celebrity. He received an award from the Democratic National Committee and the prestigious“Martin Luther King” award from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The security guard was in great demand for media interviews.

He was even recruited to play himself in the 1976 classic film All the President’s Men. The Watergate owners gave him an “insultingly” low raise, from $80 to $82.50 a week, but he ultimately left due to their “racist disrespect.”

Unfortunately, Wills was not able to parlay his celebrity into steady work. He subsisted on intermittent security work and odd jobs, and spent his remaining years caring for his ailing aunt. He died from an inoperable brain tumor on September 27, 2000 at age 52.

It seemed everybody was able to make a career, a buck or a book out of Watergate, except the man whose sharp eye opened the floodgates of history. Bob Woodward characterized his contribution this way: “He’s the only one in Watergate who did his job perfectly.”

I like Woodward’s description, but here’s the one that gave me chills when I first read it in Wills’s obituary in the New York Times. Democratic congressman James Mann of South Carolina, casting his vote for impeachment, said “If there is no accountability, another president will feel free to do as he chooses.

But the next time there may be no watchman in the night.