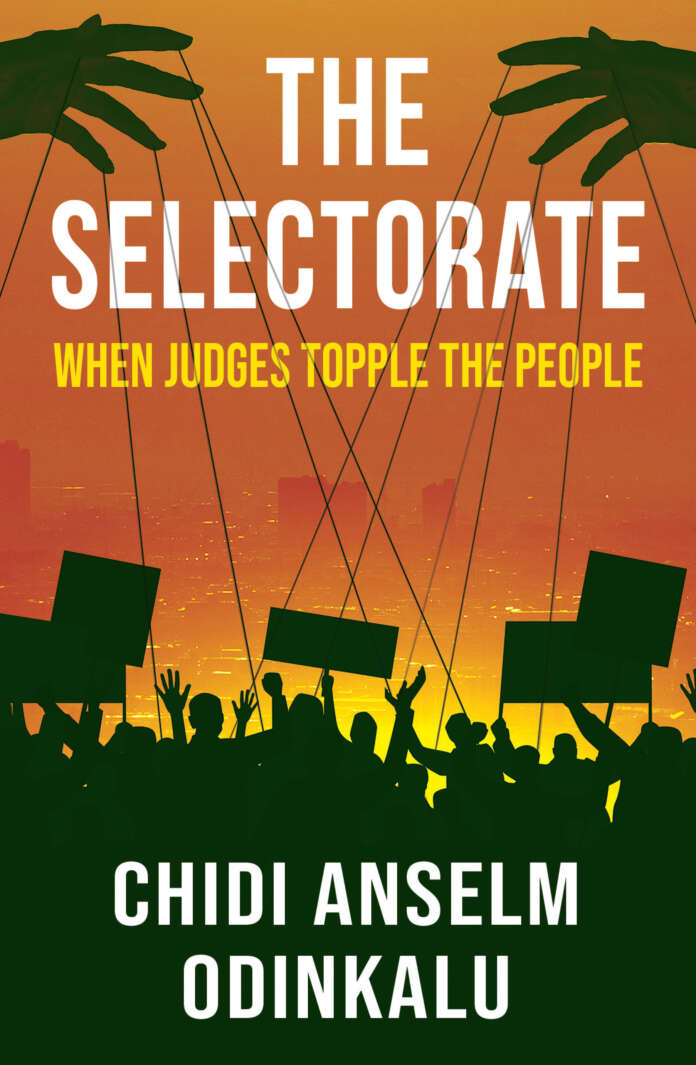

BOOK SERIAL

By Chidi Anselm Odinkalu

YESTERDAY

The author laid the groundwork for his thesis that judges, whom he calls “the selectorate”, have toppled the people in deciding who rules them. Today, he examines the concept of rule of law, the judiciary and their relationships to elective government, beginning with Albert Venn Dicey.

The Constitution’s Design

The usual fare is to begin every examination of the judiciary and rule of law in the Common Law world with an obligatory genuflection before the altar of Albert Venn Dicey and his Victorian notions of the rule of law.

These were founded on benevolent notions of predictability and equality policed under an unwritten constitution by “the jurisdiction of the ordinary tribunals.” Inherent in Dicey’s concept of the rule of law is the idea of a judiciary whose effectiveness is essentially guaranteed by their notional independence, impartiality and predictability.

Dicey’s ideas were originally published in 1893 at the onset of the European occupation of Africa. The world that Dicey described and analysed, however, did not treat people of colour as humans, and the benevolence that he took for granted as a Caucasian was unknown to the interaction between his people and colonial subjects. This certainly was the case in Africa. For present purposes, therefore, an examination of the rule of law, the judiciary and their relationship to elective government is more usefully situated in the seminal distinction drawn by Ernst Fraenkel between the “Normative State” of credible institutions and rule constraint on the one hand and the “Prerogative State” of caprice on the other.”

Democratic process, as a rule-constrained system for the transfer and exercise of power in political society, assumes the existence of what Ernst Fraenkel called the normative state of the rule of law, which he distinguished from the authoritarian prerogative state.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has similarly distinguished between a state with rule of law and judicial independence on the one hand, and the “rule of power, which is typically arbitrary, self-interested and Subject to influences which may have nothing to do with the applicable law…,” on the other.

The state with the rule of law as described can only exist where there is a reasonably independent judiciary to arbitrate and interpret the norms applicable to the democratic process. It is possible, however, for courts to be instrumentalised in a manner that uses the appearance of a norm-constrained process to engineer into existence authoritarian conditions. In many African countries, this appears to be happening.

To understand how this occurs, it is essential to stress that the role of the judiciary in the democratic process of electing government is a narrow one. As pointed out by the Supreme Court of India, the role of the courts is to oversee the validity of the electoral process in order to ensure that while the rules are certain, the outcomes of elections are uncertain or not predetermined until the votes of the people are cast and counted. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees the rights of democratic participation and to vote as the basis of legitimate government. To implement these, countries establish election management bodies (EMBs), which supervise and organise their elections and declare their outcomes.

When elections occur in this manner, they ensure that democratic legitimacy resides with the people. The Supreme Court of the United States has rightly cautioned about “the vital limits on judicial authority” concerning “the Constitution’s design to leave the selection of the President to the people, through their legislatures, and to the political sphere.” In Nigeria, the Electoral Reform Panel chaired by former Chief Justice, Lawal Uwais, similarly warned in 2008 that “care should be taken not to drag the judiciary into the political arena too often as this can affect its credibility.”

Elections are, therefore, globally accepted normatively as how the people choose who governs them but the quality of what counts for elections varies widely across the globe. This most consequential of decisions in most countries around the continent increasingly involves judges in varying degrees of intimacy, if not capture.” Following the wave of democratisation around the continent in the 1990s, this role of the judiciary was largely seen in a positive light as a source of “hope.” This verdict proved to be premature at best.

Judges are supposed to be independent of politics. Yet, the assumption exists that they can continue to make the most consequential decisions in a democracy while retaining independence from external influence. Hakeem Yusuf strongly suggests that the immersion of the judiciary in political change “seriously tasks the institutional integrity of the judiciary.”

This book argues that the immersion of judges in election dispute resolution around Africa endangers the judiciary, imperils the project of building independent institutions, and retrenches the will of the people as the foundation of legitimate government. It illustrates these triple crises with a narrative of how the immersion of Nigeria’s judiciary in election dispute resolution has over time intensely altered the traditional assumptions that underpin the judicial function as we know it but first, it is important to explain why such an inquiry is essential.

Judges, Democracy and Elections

The judicial function is now globally accepted as foundational to the role of the state and essential to Iegitimate government but its delimitation is underpinned by both fluidity and contradiction.” Notionally, the judiciary embodies the very essence of what has been described in constitutional design as “politically neutral zones.” At the African continental level, State parties to the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance (ACDEG) undertake to “establish and strengthen national mechanisms that redress election-related disputes promptly.” They also agree to “strive to institutionalise good political governance through an independent judiciary.” In the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, they equally subscribe to a “duty to guarantee the independence of the courts.”

But what does an independent judiciary entail? Ordinarily, it imports structural and institutional assumptions that recognise the judiciary as an arm of government in a scheme of separation of powers coexisting in juxtaposition with the legislative and executive branches but free from interference or manipulation from the latter two.” To assure this, formal standards of judicial independence are recognised internationally,” and instituted in the constitutions of different countries, addressing such issues as processes of appointment; security of tenure, discipline and removal; remuneration; and preclusion of reprisals or liability for exercise of judicial function. By and large, judicial independence embodies at least three complementary elements. These include adjudication by “a neutral third”, institutional insulation from political interference or pressure, and guarantees of effective coexistence as a separate branch of government.” However, around the world, the judiciary is also widely seen as a political institution, which functions in the role of political accountability.”

Howsoever the judicial function is conceived, independence is widely seen as constitutive of its being. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Independence of Judges and Lawyers has argued that judicial independence belongs to the domain of a peremptory norm of international law (jus cogens), although he stops short of explicating the elements of such a norm.

The scope and meaning of judicial independence exist in a zone of contradiction and dynamic ambiguity that encompasses institutional as well as procedural; inherent and instrumental; normative and situational; structural and behavioural; prophylactic and propositional: as well as formal and informal dimensions.

Yet, political rulers can often suborn the judiciary to legitimise themselves and the effectiveness of the judicial institution is reputedly shaped by political context. Courts and judges are at once institutions and employees of the state and yet, agents of the government. Notwithstanding its description by Baron de Montesquieu as “in some measure next to nothing,” the judiciary is nevertheless eulogised in comparative jurisprudence as the ultimate custodian of constitutional government, the “lifeblood of constitutionalism,” and as the avatar of the people against autocracy.”

The adjudication of election-related disputes tests the limits of these assumptions about the judiciary and has been delicately described as a “compromise between law and political expediency.” In many African countries, the people may vote but the question of who wins or loses the presidency is increasingly resolved as a judicial dispute in compelling spectacles of judicial pusillanimity. Uganda’s former Chief Justice, Benjamin Josses Odoki, “smiled when commenting that to nullify a presidential election would be suicidal,” suggesting that the independence of judicial decision making in any country is reflected in both the scope of judicial imagination and in its institutional psychology.

A mere seven years after this claim by Uganda’s Chief Justice, David Maraga, as Chief Justice in neighbouring Kenya, led the Supreme Court in that country to accomplish precisely that,” and less than three years later, the Constitutional Court did the same in Malawi, with a bench of judges dressed in bullet-proof vests.” It must be said that these could not have occurred under the constitutional systems bequeathed by colonialism at Independence. By the time these developments occurred, these countries had re-engineered their constitutional foundations forged in bitter experience.

But, if judges can be so powerful as to strike down election returns, it is natural to expect that assertions of their independence will not go without political pushback. Naturally, therefore, the involvement of judges in electoral adjudication makes their independence a zone of political contest.

TOMORROW…

The author discusses how the courts in Africa have overreached themselves and the consequences, citing as examples Malawi, Zimbabwe and Mali before zeroing in on Nigeria, saying “few countries have been overtaken by this trend like Nigeria.”