Introduction

When I was admitted to the Department of Political Science in 1980 as a freshman, straight from secondary school, Professor Humphrey Nwosu was one of the lecturers we encountered. He was the head of the sub-department of Public Administration, which owned the Local Government building that housed the Department of Political Science.

Though he was an energetic and ebullient man, he wasn’t exactly very popular with us for two main reasons: One, is that he normally fixed his lectures at 7 a.m. in the morning, and he never failed to show up for classes. He would in fact often be in the class before that 7 a.m., which led to some of us gossiping behind his back about a man who preferred to come jumping up and down in the class at a time in the morning that he should be keeping his wife company. The second reason Nwosu wasn’t quite popular with us was that Nigerian Universities in the 1980s and early 1990s was very ideologically driven, essentially between the Marxists (also called the ‘radical scholars’) and those who were variously called ‘bourgeois scholars’ or derided as the “educated representatives of the propertied class.”

Unfortunately, Nwosu was among those we called “bourgeois scholars.” We were told that the bourgeois scholars were not able to to appreciate the “dialectics of class struggle”, that their works were very “ahistorical”, with a “tendency to be arbitrary in their choice of analytical categories”, and that they failed to appreciate that the nature of the “productive force” and “social relations of production” were the motif forces of history. Though we knew that Nwosu made a First Class honours degree, however because we saw him as a “bourgeois scholar”, we ridiculed that accomplishment as being merely a First Class Honours in ‘Elements of Government’, not the sort of proper political science that the ‘radical scholars’ were teaching us. Mr Nwosu, on his own, blamed the ‘radical scholars’, the “Nnoli boys”, of exposing students to only one side of a complex reality. Though we regarded Nwosu as a ‘bourgeois scholar,’ we still respected him for the sheer force of his presence, or charisma if you like – unlike most of the other lecturers we regarded as ‘bourgeois scholars.’

I recall an incident with one of the ‘bourgeois scholars.’ He was teaching us something about “colonialism,” which was at that time the favourite whipping boy of the radical scholars, who made it compulsory that we should read and master such works as Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Okwudiba Nnoli’s Ethnic Politics in Nigeria, and Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. In fact, from Nnoli’s book we learnt that ethnicity in Nigeria started in the colonial urban centres and was fuelled by the colonial policy of ‘divide and rule.’ Rodney’s book squarely blamed colonialism for Africa’s underdevelopment, while Fanon’s book provided a psychoanalysis of the dehumanising effects of colonisation upon the individual and the nation.

When Nwosu left office in 1993 after the annulment of June 12 presidential election, he returned to teaching at the Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he formally retired in 1999. Nwosu has published several books and peer-reviewed articles in both local and international journals. His books include Political Authority and Nigerian Civil Service (1977); Problems of Nigerian Administration (edited, 1985)…

With our understanding of colonialism from these three books and similar ones, I think we were tolerating the ‘bourgeois scholar’, until he wrote on the black board: “The benefits of colonialism.” We felt we have heard enough. One of us from the back of the class shouted, “Whaaat?!” In anger, the entire class walked out on him, believing that he did not know enough to teach us, or was teaching us the wrong stuff, despite the fact that we were just in our first year, or ‘class One’ as someone of us liked to call it in those days.

Though we regarded Nwosu as a “bourgeois scholar”, we also respected him as an effective administrator. In fact, behind the backs of the radical scholars, we mocked their relative lack of administrative capacity, compared to Nwosu. Professor Nnoli, the leader of the radical scholars, was the head of Department of Political Science in our first year in the department.

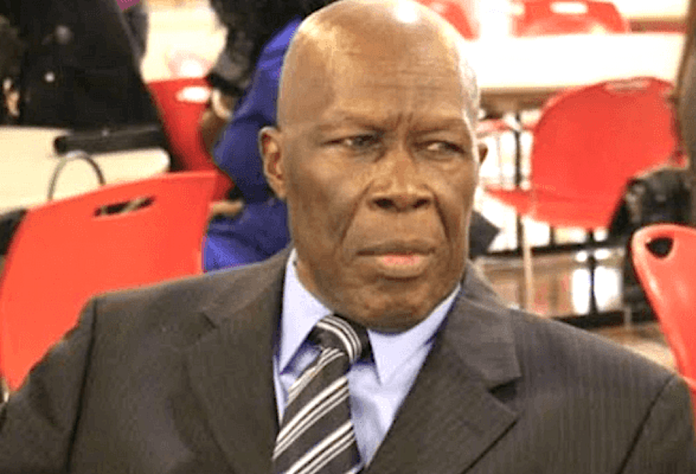

Humphrey Nwosu: a Brief Biography

Humphrey Nwosu was an astute and charismatic public administrator, academic, technocrat, and political scientist. He studied Political Science at the University of California at Berkeley, where he earned Master’s and doctoral degrees (Magna Cum Laude) in 1973 and 1976 respectively. He subsequently returned to teach at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he rose to become a full-time tenured professor. In 1986, he was appointed by the Anambra State Government to serve as Commissioner of Local Government and Chieftaincy Matters and later Commissioner of Agriculture. He was appointed Chairman of the Nigeria Electoral Commission in 1989, to replace Professor Eme Awa, his former lecturer and mentor, who had fallen out of favour with the Babangida government.

When Mr Humphrey Nwosu left office in 1993 after the annulment of June 12 presidential election, he returned to teaching at the Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he formally retired in 1999. Nwosu has published several books and peer-reviewed articles in both local and international journals. His books include Political Authority and Nigerian Civil Service (1977); Problems of Nigerian Administration (edited, 1985); A Book of Reading; Introduction to Politics; Moral Education in Nigeria; Conduct of Free and Fair Election in Nigeria: Speeches, Comments and Reflections (1991) and Laying the Foundation for Nigeria’s Democracy: My Account of June 12, 1993 Presidential Election and its Annulment (2008). Mr Humphrey Nwosu, breathed his last on Thursday, 24 October, in the United States of America, at the age of 83

What Does It Mean to Be a Reformer at the Crossroads?

A reformer is a change agent who is deliberate and intentional about improving the way things work. As an expression, the imagery often invoked is that of an intersection of two roads in which a person has to make a decision on which of the roads to take. Essentially, it means being at a stage when one has to take a critical or an important decision.

Humphrey Nwosu’s challenge was not just in helping to manage a transition to a full civilian rule, but also to facilitate the process of de-militarisation – that is the military handing over power to civilian authorities and accepting subordination to a civilian authority. This means that unlike the electoral bodies since 1999, which dealt only with the political class and its mode of competition for power, Nwosu had to deal with two humongous groups – the political class and the military establishment…

The above raises two important questions: Which reforms are we talking about in relations to Mr Nwosu? And at which crossroads?

Though it is obvious that Nwosu, given the number of public positions he had held, would have been at several crossroads, for most Nigerians, he is known for his role as the chairman of the National Election Commissions from 1989 to 1993. So which crossroads are we talking about?

Mr Nwosu’s Crossroads

Mr Humphrey Nwosu’s challenge was not just in helping to manage a transition to a full civilian rule, but also to facilitate the process of de-militarisation – that is the military handing over power to civilian authorities and accepting subordination to a civilian authority. This means that unlike the electoral bodies since 1999, which dealt only with the political class and its mode of competition for power, Nwosu had to deal with two humongous groups – the political class and the military establishment, including a faction of that establishment which did not want to lose its privileges by accepting a handover to a civilian political class.

The job of being the country’s chief electoral umpire is often called a poisoned chalice, in which rarely any umpire would come out of it with his reputation intact (Professor Jega, who organised the 2015 election, was mostly lucky that Jonathan conceded defeat). If just dealing with the political class makes the job of the chief electoral umpire to be a poisoned chalice, you can then imagine what it means to be an electoral umpire for both the political class and a politicised military.

De-militarisation would often raise the question of de-politicisation. How do you professionalise soldiers who had become used to political power and its appurtenances and to being superordinate to civilian authorities? As Elaigwu (2015:232) argued, “the demilitarization of the polity without adequate de-politicisation of the military is an invitation to chaos; yet paradoxically, that process of de-politicisation of the military involves the politicization of the military”.

Essentially, Babangida’s transition programme, in which at a point the country was running a diarchy, meant that the military as an establishment had become more politically conscious and was factionalised between those who wanted a handover to a civilian government and those who resented such. In fact, Babangida, in his recent autobiography, admitted that much when he declared that “there were fears, even at that early stage of the transition programme, that some members of the top hierarchy of the military were reluctant to relinquish power” (Babangida, 2025: 258).

Jideofor Adibe is a professor of Political Science and International Relations at Nasarawa State University and founder of Adonis & Abbey Publishers. He can be reached at: 0705 807 8841 (WhatsApp and Text messages only).

This was originally presented at a Colloquium on the Life and Times of Professor Humphrey Nwosu at Abuja on 25 March.