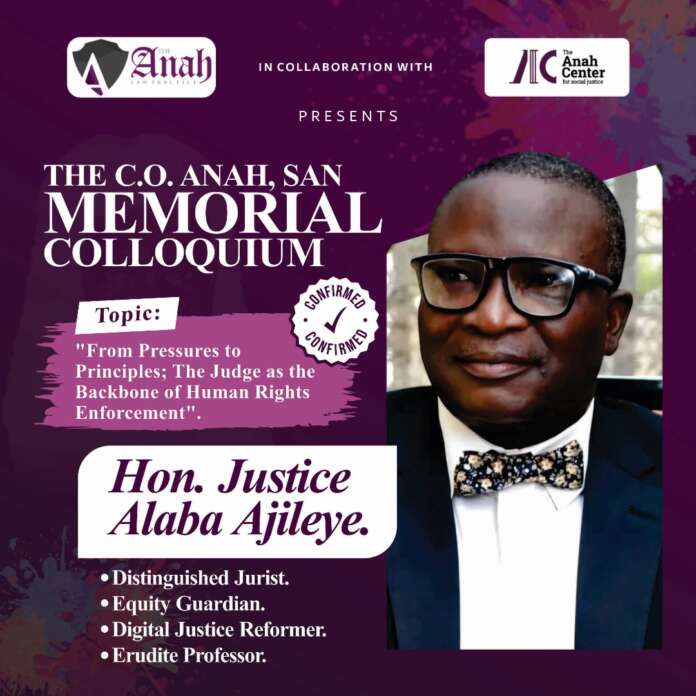

Full text of Hon. Justice (Prof.) Alaba Omolaye-Ajileye’s (rtd) paper delivered at 4th C.O. Anah SAN, memorial colloquium

FROM PRESSURE TO PRINCIPLES: THE JUDGE AS THE BACKBONE OF HUMAN RIGHTS ENFORCEMENT.

BY

HON. JUSTICE (PROF.) ALABA OMOLAYE-AJILEYE (rtd) PhD, FCIMC

FORMER HIGH COURT JUDGE

VISITING PROFESSOR

NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY

Protocol

Appreciation

Preamble

I have been asked to speak on the topic: From Pressure to Principles: The Judge as the Backbone of Human Rights Enforcement. This topic underscores the role of judges in upholding human rights in cases where they (the judges) are expected to provide remedies for victims of abuse of fundamental human rights. It underscores the point that for judges to effectively enforce human rights, they must maintain independence and impartiality. They must demonstrate character and courage to make decisions based solely on the law without external pressure or biases.

The Notion of Fundamental Human Rights

The notion of fundamental human rights derives from the acknowledgment of the fact that there are rights are inherent, universal and inalienable in man that every individual possesses simply by virtue of being human. Nobody, power, or authority confers such rights. They are not donated by the government and cannot be capriciously taken away by it. They include, amongst others, rights to life, liberty, fair hearing, freedom from torture, or degrading treatment; right to equality and non-discrimination; freedom of expression, thought and conscience etc. These rights are essential for human dignity, freedom, and well-being. Therefore, whenever a case of the enforcement of human rights comes before a judge for adjudication, something should speak to the conscience of the judge that it is not a matter that should be treated with levity. Judges must provide guidance on human rights issues by making pronouncements that will help to prevent abuse.

I am pleased to be speaking about the pressures judges face in their work. I am also pleased that as a retired judge, I can now share my thoughts freely without concern for repercussions from the National Judicial Council. Drawing from my nearly two decades of experience on the High Court bench, I can now provide practical insights, rather than hypothetical or academic scenarios. That is what I have come to do here. I have no lecture to deliver. I have no theory to propound. I have no pontification to make, but I have experiences to share.

The Mandate of Judges to Administer Justice

Let the point be made, as a threshold issue, that judges, in upholding their sacred duty to administer justice, are mandated to adhere to ethical principles outlined in the Code of Conduct for Judicial Officers. Again, upon taking office, judges swear an oath to impartially dispense justice to all individuals, unaffected by fear, favoritism, affection, or ill-will. This commitment underscores the importance of integrity, impartiality, and fairness in the process of adjudication.

Of all the attributes a judge is required to possess, to perform his or her role as backbone of human right enforcement, I consider two as towering and outstanding. They are character and courage. Character and courage are indeed the most essential attributes for judges. A judge with strong character and courage is well-equipped to uphold all the requirements of ethics and codes of conduct. Judges with strong character possess high moral integrity, honesty, and ethics. Character-driven judges will remain unbiased and fair in their decision-making. Such judges also inspire confidence in the justice system. In the same way, courageous judges make decisions independently, without external influence. Judges with courage can make difficult decisions, even in the face of the most scurrilous criticism or pressure.

The Pressure Judges Face

I had the fortune (I will never call it a misfortune) of handling many sensitive and high-profile cases while on the bench. Some of those cases put me in direct confrontation with the government, such that I was tagged as an anti-government judge! Such cases also put my career and life on the line. Sometimes, I had to go into the trenches to ensure that the independence of the judiciary was maintained and justice dispensed. Reflecting on my active years on the bench, I thank God that I survived all the vicissitudes. To the glory of God, my career came to a glorious end, and I am alive today to share my chequered experiences with you.

It’s all about the justice and independence of the Judiciary, which, I believe must be preserved in all circumstances! The concept of Independence of the Judiciary is not an esoteric term. In the context of our discourse, it is seen in light of the simple definition provided by the International Commission of Jurists (“ICJ”): “That every judge is free to decide matters before him in accordance with his assessment of the facts and his understanding of the law without any improper influence, inducement or pressures, direct or indirect, from any quarter or for whatever reason.”[1] The phrase: ‘from any quarter or for whatever reason’ is underscored. It includes the judge himself who may not be free from his or her own timidity and timorousness. In this vein, judicial independence is not just a jurisprudential notion. It is an expression of commitment to justice, freedom, and rule of law. An independent and impartial Judiciary is an institution of the greatest value in a democratic society required by law. It is an essential pillar of liberty and the rule of law.

In some climes, the battle for independence of the Judiciary had been won, though, not on a platter of gold, but had been the work of ages to establish, and the sacrifices of courageous men to attain. In Nigeria, it is still work in progress. That is why Nigeria needs courageous judges who will not compromise justice on the altar of inducement, threats or intimidation; Judges who will make decisions solely based on the law without fear and favour; judges who will bravely face threats or intimidation and prioritize the integrity of the justice system.

Unarguably, judges face a multitude of pressures that often influence their decisions. These pressures come in different forms, dimensions, characters, and colours. They also come from friends and relations who may be acting as emissaries or conduit. These people are usually carefully chosen for such nefarious and ignoble assignments on account of their relationship with the judge or the presumed influence (undue influence) they think they can bring to bear on him or her.

Pressure from Executive Arm of Government

By far, the most worrisome exertion of influence on judges comes from the executive branch of government. There are people in government circles whose perspective of the judiciary appears to be distorted, viewing it (the judiciary) as a subordinate department or agency rather than an independent branch of government. This mindset leads them to wrongly perceive judges as mere instruments or tools expected to implement their directives without question. I experienced some of these pressures during my career as a judge. Due to constraints of time, I will highlight two notable cases to demonstrate my points. They are, Eri & Anor v Kogi State House of Assembly & 3 Ors (2009) All FWLR (Pt. 469) 343 and Ajanah & Anor v Kogi State House of Assembly & 4 Ors (Reported in my book: In the Interest of Justice: Excellence in Judgment Writing. Pp. 97 – 126).

The two cases had to do with the removal of Chief Judges. The provision of Section 292 of the Constitution prescribes the ways judicial officers can be removed. To me, the provision is fluid, yet it remains unaltered till date. Both the Executive and Legislature often take advantage of the fluidity of the provision of the Constitution to abuse the same with recklessness. Twice in Kogi State, attempts were made to remove Chief Judges. I had the honour of handling the two cases.

Constitutional Provisions for Removal of Judges

The truth remains that the Constitution simply requires the Governor to remove a Chief Judge upon an address supported by a two-thirds majority of a House of Assembly to get the Chief Judge of a state removed. The relevant provision states:

Section 292

- A judicial officer shall not be removed from his office or appointment before his age of retirement except in the following circumstances –xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

(ii) Chief Judge of a State, Grand Kadi of a Sharia Court of Appeal or President of a Customary Court of Appeal of a State, by the Governor acting on an address supported by a two-thirds majority of the House of Assembly of the State…Praying that he be so removed for his inability to discharge the functions of his office or appointment (whether arising from infirmity of mind or of the body) or for misconduct or contravention of the Code of Conduct.[2]

It looks like a simple process to remove a Chief Judge, and politicians wrongly consider removal of Chief Judges as a political issue. Accordingly, it is easy to allege misconduct against a Chief Judge on flimsy grounds because misconduct is not defined under the Constitution for purposes of Section 292. Misconduct, therefore, becomes an eccentric word, often abused, and the abuse is such that a little disagreement between a Governor and Chief Judge is jointly treated by both the Executive and Legislature as ‘’misconduct” under Section 292 of the Constitution. For instance, the allegation against the late Justice Nasiru Ajanah (CJ, of blessed memory) was that he failed to release the payroll of judicial staff to the Secretary to the Government of Kogi State for a pay parade of civil servants in the state as directed by the Governor. The response of the late CJ Ajanah to the SGS’s letter was a polite decline to the request and a gentle reminder that the Judiciary was not a parastatal or department of the Government of Kogi State but one of the three arms of the government. What followed was the passage of a Resolution by the Kogi State House of Assembly for the removal of the CJ.

In my judgment, I stated that I found a dubious and conspiratorial siege of both the Executive and Legislature of Kogi state against the Head of the Judiciary of the state. I added:

There also appears to be an unholy alliance in which the Legislature subjugated itself to the overbearing powers of the Executive to subdue the Judiciary under the guise of carrying out a phony investigation.

The Pressure Came – Eri’s Case

No 1 – Subtle Threat & Intimidation

- Emissaries (Distinguished and highly respected individuals).

- They reminded me of the fact that Justice Eri was at the twilight of his career while I was at the threshold of mine. [Justice Eri had only three months to retire from judicial service when he was purportedly removed by Kogi State House of Assembly. I was barely two years on the bench.

- Why can’t you allow another judge to hear the case? Are you the only judge who can do it?

Such were messages they came to deliver. I was not moved. I was firm in my stand that if it was accepted that the case must be heard by a judge, why not me? Their expectation was that I would just come to court one day, give a flimsy excuse and withdraw from the case. This didn’t happen. So, their subtle threat and intimidation did not work.

NO 2 – Thou shall not deliver the judgment

I completed the hearing of CJ Eri’s case in record time [within 40 days]. The case was filed on 7th April and judgment delivered on 18th May 2008. Justice Eri had less than 45 days to retire. There were many interlocutory applications designed to delay the hearing case. What I did was to consolidate the hearing of all the interlocutory applications and delivered the rulings along with the judgment.

Pressure –

- Order to adjourn the case sine die.

- I went into trenches. I knew my life was in danger.

- Justice Eri obtained justice as his dismissal was nullified.

Compare Justice Eri’s case with the case of Justice Walter Onnoghen (CJN’s as he then was).

- The Code of Conduct Tribunal granted an ex-parte order for Justice Onnoghen to step aside as the Chief Justice of Nigeria and Chairman of the National Judicial Council, and for the President to swear in the next most senior Justice of the Supreme Court as acting Chief Justice of Nigeria, thereby removing the appellant from office.

- Justice Onnoghen before and during the trial, raised objections challenging the jurisdiction of the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT), to hear and determine the matter same having not been brought by due process of the law, as the appellant being a judicial officer, ought to have been reported to the National Judicial Council first whose findings and recommendations would determine the action(s) to be taken against him.

- The Tribunal ruled against him.

- The former CJN filed three appeals namely: (1) CA/A/375c/2019 (2) CA/A/376c/2019 and (3) CA/A/377c/2019. The appeals were filed in 2019 but were not determined by the Court of Appeal until November 4, 2024, after President Buhari left power.

- Whatever amount of money he might have received as damages or whatever the question remains: Did the former CJN obtain justice?

CJ Ajanah’s case

This was one case that would go into my record as one in which I experienced the crudest form of pressure.

- Intimidation to life.

- Withdraw of Police security from my court.

- Thuggery.

Principles

Through determination and perseverance, I overcame the hurdles that stood in the way of justice in the two cases and delivered conclusive judgments, advancing crucial legal principles and providing clarity on key issues.

Principle No 1 – Only the National Judicial Council is constitutionally empowered to recommend the removal of a Chief Judge or Judicial Officer. The substratum of justice would be destroyed if a legislative house is allowed to discipline judicial officers.

When I heard Justice Eri’s case in 2008, there was no clear precedent for me to follow to establish that the power of the Governor to remove the Chief Judge of a state went beyond the application of Section 292 of the Constitution. I was constrained to strain the letters of the constitution and proactively take the matter beyond the scope of Section 292. I treated the act of removal of a Chief Judge as a disciplinary action and brought it under Item 21 (d) of the Third Schedule to the Constitution. This is what I said:

It is a cardinal principle of our Federation under the 1999 Constitution that there is a separation of powers, subject to checks and balances, between the Legislature, the Executive, and the Judiciary. (See sections 4, 5, and 6 of the Constitution). Under Item 21 of the Third Schedule to the Constitution, the National Judicial Council (NJC) is empowered to exercise disciplinary control over all judicial officers in Nigeria. Where a Chief Judge of a State is to be removed, for instance, for whatever reason, it is the National Judicial Council that is empowered to make recommendations to the Governor of that State under Item 21 (d) of the Third Schedule. I suppose that before the National Judicial Council makes any recommendation, it is expected that the NJC will investigate the complaints against such a Chief Judge or any

Judicial Officer for that matter. It, therefore, follows that the power of investigation inseparably goes with the disciplinary power of the National Judicial Council under Item 21 of the Third Schedule of the Constitution.”

I, then, remarked further:

…This is how it should be because there is something so monstrous and outrageous in allowing anything to the contrary. Indeed, to allow a Legislative House, as the 1st defendant, to investigate and/or discipline judicial officers would destroy the very substratum of justice and introduce a system of servitude, utterly inconsistent with the constitutional independence of judges… Let it be said here, therefore, loud and clear, that no Legislative House, the 1st defendant inclusive, has any oversight function over any judicial officer in Nigeria. This is a basic truth that must be accepted by the defendants. Applying this principle to this case, means, upon the receipt of the petition written against the 1st claimant by a body called Movement for Transparent Government, the 1st and 2nd defendants ought to have directed the petition to the appropriate authority which, in this case, is the National Judicial Council, the body charged by the Constitution to investigate complaints against judicial officers. They (the 1 and 2 defendants) ought not to have wasted their precious legislative time debating the petition, in the first place, let alone setting up an ad-hoc committee that is incompetent to handle such matters. It is hoped that this hint will be taken against future occurrences.

Principle No 2 – A House of Assembly cannot usurp the adjudicatory power of the Judiciary.

In CJ Ajanah’s case, I held:

I find that the committee [of the House] has not been constituted for a permissible purpose under the Constitution but to witch-hunt the claimants. Resolution of an “impasse” between two arms of Government falls outside the purview of the powers of a legislative house. Section 128 of the Constitution is not designed to enable the Legislature to usurp the general adjudicative powers of the Judiciary under Section 6 of the same Constitution. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd defendants, in this case, ought not to have wasted their precious legislative time debating the petition of the Secretary to Kogi State Government, Exhibit KGS 1, in the first place, let alone set up an Ad hoc committee that is grossly incompetent to handle such matters.

Omolaye-Ajileye, J., in Hon. Justice Nasir Ajanah & Anor. V. Kogi State House of Assembly& 4 Ors (Suit No HC/uCV/2018)

Principle No 3 – Disobedience to court orders is a threat to democracy

When issues involving disobedience of court orders arise, it must be appreciated that they are matters that transcend the claims and interests of the parties before the court. They even go beyond being just an affront to the judge who made the order. Something more fundamental is involved. We are here talking about a potent destabilizing factor of the social equilibrium. They are issues that frontally attack and challenge the whole concept of judicial powers vested in the courts under the Constitution and a calculated act of subversion of peace, order, and good government. Indeed, disobedience of court orders is a big threat to democracy.

Omolaye-Ajileye, J., in Hon. Justice Umaru Eri & Anor. v. Kogi State House of Assembly & 3 Ors. (Suit No HC/KK/002CV/2008).

Principle No 4 – Government ought to govern by example and respect the rule of law

We live in a country where the government professes to the whole world that it is operating under the rule of law. One important way to encourage respect for the rule of law is for those in authority to demonstrate, by their conduct, that the law they make, execute, or administer, as the case may be, also binds them. They must validate the fact that they do not constitute an exceptional group that towers above the law. Indeed, it is the challenge of the government to govern by example.

Omolaye-Ajileye, J., in Hon. Justice Umaru Eri & Anor. v. Kogi State House of Assembly & 3 Ors. (Suit No HC/KK/002CV/2008).

Conclusion – The Type of Judges we need

When all is said and done, the pertinent question here is, what type of judges do we need to act as backbone of human rights enforcement? I cannot find a better answer to this question than the words expressed by Donald R. Cressey when he said:

We need judges learned in the law, not merely the law in books but something far more difficult to acquire, the law as applied in action in the courtroom, judges deeply versed in the mysteries of human nature and adept in the discovery of the truth in the discordant testimony of fallible human beings; judges beholden to no man, independent and honest and equally important, believed by all men to be independent and honest; judges, above all, fired with consuming zeal to mete out justice according to law to every man, woman, and child that may come before them to preserve individual freedom against any aggression of government; judges with humility born of wisdom, patient and untiring in the search for truth and keenly conscious of the evils arising in a workaday world from any unnecessary delay.”[3]

I should finally add that the type of judges we need are those who will see every case before them, including cases of enforcement of human rights, as a journey in which destination is justice; judges who, in the course of the journey, will see themselves as pilgrims insulated from all forms of pressures around him either in the form of inducement or intimidation etc. Judges who would declare as John Bunyan declared:

He who would valiant be

‘Gainst all disaster,

Let them in constancy

Follow the master.

There’s no discouragement

Shall make them once relent

Their first avowed intent

To be a pilgrim.

I rest my case! Thank you for listening

[1] 3 25026 CIJL Bulletin, April-October 1990. Retrieved from: https://www.jsc.org.zw/upload/Speech/Chief%20Justice’s%20Paper%20for%20SACJF%20Conference%20-%20Mozambique%20-%2024%20October%202022.pdf on 21/5/2025.

[2] : https://jurist.ng/constitution/sec-292

[3] 31 DR Cressey “Crime and Criminal Justice” Quadrangle Books Chicago 1971 p.263. Quoted from Luke Malaba (2021) Judges Induction Compendium, 1st ed. Retrieved from: https://www.jsc.org.zw/upload/Publications/JUDGES’%20INDUCTION%20COMPENDIUM%20FIRST%20EDITION%202021.pdf