The energetic and skilled orator who delighted the Queen but clashed with Thatcher over sanctions on apartheid South Africa

At any Commonwealth meeting in the 1980s Sir Shridath Ramphal would be on hugging terms with most people in the room. And if that wasn’t the case with Queen Elizabeth II, the organisation’s secretary-general was said to have got on famously with the British monarch. It was only when he found himself under the gimlet eye of Margaret Thatcher that the bonhomie ended abruptly.

Matters came to a head at the 1985 Commonwealth heads of government meeting in Nassau, in the Bahamas. The Guyana-born Ramphal had been an enthusiastic advocate of imposing sanctions on apartheid South Africa. For her part, the British prime minister regarded him as a civil servant who was overreaching his brief.

Thatcher would later bow to pressure to impose economic sanctions on South Africa, but was not ready to do so at Nassau. “I noted that they were busy trading with South Africa at the same time as they were attacking me for refusing to apply sanctions,” she recalled in her memoirs. “I wondered when they were going to show similar concern for the abuses in the Soviet Union … I wondered when I was going to hear them attack terrorism. I reminded them of their own less than impressive records on human rights.”

A small, rotund man who exuded geniality, Ramphal had similar views on the Commonwealth to the Queen — though he said it was anachronistic for it to be led by a monarch — and he was given almost unbridled royal access. “She transcended the barriers of race, colour and caste very easily, and she was never lofty or remote,” he said. “In all my 15 years, I never met a prime minister or a president — Marxists and republicans included — who did not set the greatest store by the 20 minutes she spent with each of them at our heads of government meetings.”

Such royal favour was perhaps one reason Thatcher’s personal criticism of the liberal diplomat, known as Sonny, was less vehement than it might have been. The same could not be said for her husband, Denis. “He and I didn’t get on,” Denis recalled. “He was so left-wing. I used to say: ‘Sonny Ramphal, you really are a terrible man … You do more harm than good.’ He came back after the election and I said: ‘You’ve got us for another four years, Sonny. I hope to Christ we’re not going to have you.’”

Emboldened perhaps by another gin and tonic, Denis continued: “Who do you think is worse? Sonny bloody Ramphal or Ma bloody Gandhi?”

However, to a whole political generation of the developing world, Ramphal was a passionate and articulate advocate of their demands for a fairer world — even if what he was campaigning for did not always lead to one. As secretary-general of the Commonwealth between 1975 to 1990 he helped to broker the decolonisation of Rhodesia into Zimbabwe, and arguably played no small part in helping to abolish apartheid in South Africa.

Shridath Surendranath Ramphal was born in New Amsterdam in British Guiana, now Guyana, in 1928. His great-grandmother, exiled from India after refusing to immolate herself on her husband’s funeral pyre, had come to Guyana to work on a sugar plantation owned by John Gladstone, father of William, the Liberal prime minister.

Ramphal’s father, James, who was educated by Canadian Presbyterians and converted to Christianity, was a teacher and member of the capital Georgetown’s middle class, able to give his son a solid education — first at a school for the children of the elite in Georgetown and then at the University of London. James was the first Guyanese to be appointed to a government position when he was made a commissioner in the department of labour after the outbreak of the Second World War.

Ramphal read law at King’s College London, and in 1951, the same year he married Lois King, an English nurse, he was called to the Bar at Gray’s Inn and became a legal probationer for the colonial office. King died in 2019. Ramphal is survived by their two sons and two daughters.

Shortly after Ramphal entered the chambers of Dingle Foot, the elder brother of Michael, the future Labour leader, the colonial office dispatched him to Kenya to help to deal with the Mau Mau emergency. His patron soon brought him back and secured him an appointment as crown counsel in Guyana instead.

An able lawyer, a quick-witted politician and a gifted speaker, he spent a year at Harvard Law School in 1962 but was soon back in Guyana, where he drafted the nation’s independence constitution. Proclaiming himself a proud West Indian, he held a variety of ministerial positions, including as foreign minister under the newly elected black Guyanese prime minister, Forbes Burnham.

Ramphal used his office to carve out for himself a wider role in the councils of the developing world. He was twice elected vice-president of the UN general assembly and led his country’s delegation to the UN every year between 1967 and 1974. During his chairmanship of a meeting in Georgetown of the foreign ministers of the Non-Aligned Movement — states that would not ally with the US or Soviet Union during the Cold War — in 1971 he steered them towards more radical and articulate criticism of western neglect and exploitation of the developing world.

A Commonwealth heads of government meeting in Jamaica three years later gave him a bigger opportunity. There he was appointed secretary-general, succeeding the first holder of the post, the Canadian diplomat Arnold Smith, who had fought a tenacious but modest battle to build up the secretariat as a focus of the institutional Commonwealth against the resistance of Whitehall.

Ramphal’s approach was anything but modest. He steadily expanded the size and scope of the secretariat, consistently advocated measures to increase the Commonwealth’s range of interests and particularly its services to its developing members.

The African member nations held particular opportunities. At the heads of government meeting in Lusaka, Zambia, in 1979 he was among those who called on Thatcher, recently elected, to accept independence for Zimbabwe. Throughout the Lancaster House negotiations that followed, Ramphal was in the margins, pressing the views of the developing Commonwealth countries. In some eyes he was helpful and constructive; in those of Lord Carrington, the foreign secretary, he was “cocky and meddlesome” — Carrington claimed that Ramphal helped Robert Mugabe to gain his election victory.

From Zimbabwe, Ramphal turned his attention to South Africa, and he did much to orchestrate Commonwealth concern for apartheid and oppression there over the next ten years. When Nelson Mandela came to power he showed his appreciation by quickly bringing his country back into the Commonwealth.

Ramphal had for some time had his eye on bigger things: he wanted to be secretary-general of the United Nations and had been building a broader international reputation, involving himself in a series of initiatives of the international great and the good, starting in 1977 with the former German chancellor Willy Brandt’s group on international development and moving on to the Swedish prime minister Olof Palme’s study of disarmament and security.

He first campaigned to be UN secretary-general in 1981, and although he had the support of Pierre Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister, he was not appointed. He claimed afterwards that it was his criticism of the organisation that had deprived him of the prize, but Carrington had famously said he would swim the Atlantic to prevent Ramphal getting the job.

Ramphal turned back to the Commonwealth and to yet more international commissions: humanitarian issues, environment and development, the problems of the developing world, and questions of global governance. In many ways the commissions suited Ramphal better: he had a talent for words and instinct both for the real needs of the poor and for the fanciful ambitions of their spokesmen and women. Some accused him of being just as meretricious — all posture and little substance — but people listened to him. Even Thatcher confessed that just occasionally his cheerfulness could sweep her off her feet.

By the time the Commonwealth heads of government met in Kuala Lumpur in 1989, Ramphal was approaching the end of his third term as secretary-general. At the end of his service the British government put his name forward to Buckingham Palace for appointment as Knight Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) but it was typical of his fractious relationship with Britain that, days after a generous farewell dinner in his honour at 10 Downing Street, a London newspaper reported him as having criticised his hostess, Thatcher.

He was still only 62 — and as energetic and full of ideas as ever. He was chairman of the West Indies Commission, president of the World Conservation Union and an active chancellor of two universities: the West Indies and Warwick. He travelled restlessly and audiences of the like-minded hung on to his words.

Some argued that he used his oratorical and political skills to enhance the bargaining power of the poor countries against the rich. But there were few who took him as seriously as he thought he deserved, and after each of his rhetorical acts there remained the facts of power and poverty, wealth and impotence.

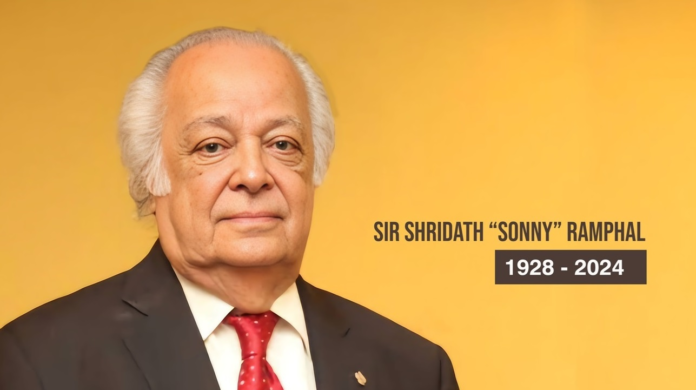

Sir Shridath Ramphal, Commonwealth secretary-general, 1975 to 1990, and lawyer, was born on October 3, 1928. He died on August 30, 2024, aged 95

Culled from The Times