By Bolaji Tunji (First published in The Guardian on Saturday in 1999)

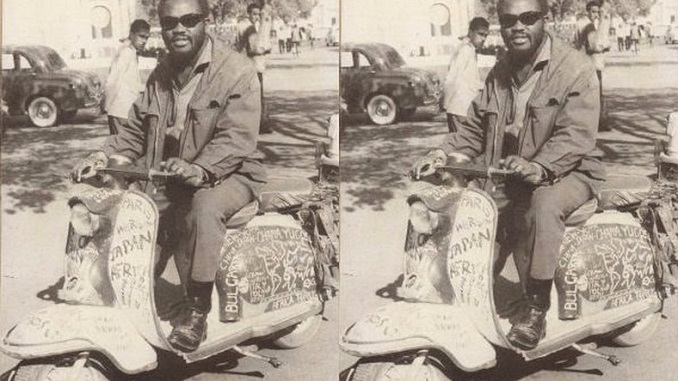

OLABISI Ajala. The name may not readily ring a bell to the younger generation of Nigerians, but the older generation would certainly remember him as the happy-go-lucky bearded globe-trotter and socialite who put the nation on the world map, as he traversed the globe on his motor scooter. Ajala explored the unexplored and charted the hitherto uncharted areas of the world.

He wined and dined with heads of state and leaders including the late Alhaji Tafawa Balewa, first Republic Prime Minister of Nigeria; the late Paudit Nehru of India; the late Abdel Nasser of Egypt; the late Golda Meir of Israel; the late Marshall Ayub Khan of Pakistan; the late President Makarios of Greece; the late General Ignatuis Acheampong of Ghana and the late Odinga Oginga, one-time vice-president of Kenya. The list, indeed, is endless.

But on the February 2, 1999, the man fondly known as “Ajala travel” died. He died in penury. The world famous Ajala died unsung and unrecognised. His grave in central Lagos is no different from any other. For more than a year, Ajala suffered. He had a stroke which paralysed his left limb. But his army of children were not there to give him succour.

He only had two of them around, Olaolu Ajala, a 20-year-old student of Baptist Academy, Lagos, and Bolanle Ajala, his 17-year-old daughter who had just finished her senior secondary education at the Baptist High School, Bariga, Lagos. With him also in his last hour was another teenager, 14-year-old Wale Anifowoshe. Wale was especially fond of him. He kept all Ajala’s money, the little there was.

Some of his children who could not be with him include Dante, Femi, Lisa and Sydney all of whom are based in Australia. They are thechildren of his Australian wife, Joan. Some of his other children are also spread around the globe. There are Taiwo and Kehinde in the United States as well as Bisola in England. But all were not around to bid their father a final goodbye except Olaolu and Bolanle.

Indeed, it is a sad end for a man whose scooter is now a national monument. None of his numerous wives was around to bid him goodbye tothe world beyond. His first wife, Alhaja Sade, could not find time during the year-long sickness of her husband until he finally died. She lives in Ikotun, a suburb of Lagos. “We told her that he was sick and she told us she would come, but we never saw her,” Olaolu said.

He was not sure whether she is aware that her husband is dead. Joan, only got in touch with him through correspondence. There are also Mrs. Toyin Ajala in England and Mrs. Sherifat Ajala, mother of his last daughter, Bolanle. But they were not around to tend to the man when he was battling with his sickness. A neighbour in Bariga who spoke on condition of anonymity said: “He could have survived if he had had adequate care.” Adequate care was indeed far from the late globe-trotter. In no other place was this manifested than his residence, a rented apartment in a two-storey building on Adenira Street, Bariga.

Climbing two flights of stairs to the top floor, one is immediately confronted with the way life had treated Ajala. A passage leads into a 16-by-12 feet sitting room. The sitting room, devoid of carpet has a table with about five locally made iron chairs in a corner. This, the reporter gathered, serves as the dining table. An old black and white television set sits uncomfortably in all ill-constructed shelf. The cushion on the sofa hurts the buttock as it has become flat. The curtains on the windows of the two bedroom flats show signs of old age. It is indeed a story of penury.

But his two children in Nigeria still hold fond memories of their father. They eagerly answered questions and consulted calendars to give precise dates which they had marked on the calendar. The mantle of responsibility falls on Olaolu who printed the poster that gave the details of his father’s death. Narrating the last days of his father, Olaolu told {The Guardian On Saturday} that he had a stroke on June 18, last year. “On that day, I had gone to school. When I came back, he told me he fell down on the balcony. We went to call a doctor about three blocks away. It was the doctor who told us that he had a stroke.”

According to Olaolu, medications were prescribed. “We bought the drugs and we followed the doctor’s instruction that we should allow him to rest.” The doctor, who came from a private hospital further advised the children to get their father a physiotherapist. “We got one for him at the Igbobi Orthopaedic Hospital and he was always coming home to give him therapy. And we noticed that he was getting better.”

But the picture changed after three months of home medication. “After three months, we realised that he had relapsed. He was able to walk if he held on to someone. But this suddenly stopped. He could no longer walk.” That was when divine intervention came from a family friend, Morufu Ojikutu, who arrived from Germany. “He advised that we should take him to the hospital when he saw his condition. He also gave us money for his treatment,” Olaolu said.

The reporter gathered that what really stopped the ailing Ajala from going to the hospital was the lack of funds. Says Olaolu: “When he got sick, he did not have money but later my sisters and mum sent in some money for his treatment. And it is this that we spent to keep ourselves together.”

But Bolanle chipped in that at times, money sent to their father doesn’t get to him. “Brother Femi (his second son) sent him £500 but he never received it and that was what he was harping on until he died”, she said.

In spite of the lack of funds, Olaolu believes that he died because he did not get quick medical attention. “When Mr. Ojikutu came, it was already too late. I think he also knew he was about to die and he did not want to die at home. That was why he insisted that he should be taken to the hospital.” Ajala eventually ended up at the General Hospital, Ikeja. “He was there for 11 days. Prior to his death, his younger sister also deposited money with an aunt at the hospital to take care of him,” Olaolu said. It was gathered that before his death, Ajala had demanded that his relatives should bring a more comfortable chair, radio and orange juice. “But when the things were taken to him on February 2, he was already dead,” Olaolu said.

According to Wale, who was with him in the hospital, Ajala had been restless since the weekend before his eventual death. “When he first got to the hospital on January 25, he was always playing and joking with the people in the ward. But from Sunday, January 30, he could not breathe very well. He was always breathing through the mouth until he died on Tuesday, February 2,” Olaolu said.

`Ajala explored the unexplored and charted the hitherto uncharted areas of the world. He wined and dined with heads of state and leaders including the late Alhaji Tafawa Balewa, first Republic Prime Minister of Nigeria; the late Paudit Nehru of India; the late Abdel Nasser of Egypt; the late Golda Meir of Israel; the late Marshall Ayub Khan of Pakistan; the late President Makarios of Greece; the late General Ignatuis Acheampong of Ghana and the late Odinga Oginga, one-time vice-president of Kenya. The list, indeed, is endless.