A new book about marathon champion Gideon Hagack tells a strange and little-known story of sporting injustice.

By Oluwashina Okeleji

A murmur of excitement went up from the crowd inside the National Stadium in Lagos as an implausible rumour began to filter through.

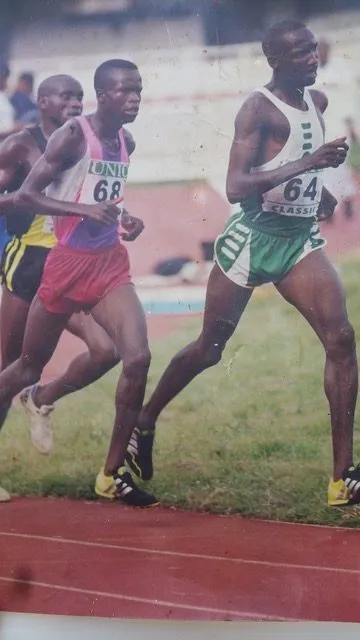

The blast of the siren signifying the imminent arrival of the marathon leader only served to heighten the anticipation, and when the two runners at the top of the pack entered the bowl, the murmur rose to a roar.

Out in front by mere metres was local man Gideon Hagack, locked in a sprint finish with Kenyan Benson Muriuki with 300 metres left to run. Hagack just held on to come first.

His victory at the Milo International Marathon in Lagos on October 9, 1994, set off jubilation in the stands. But while still dressed in his running gear, he was arrested for cheating, held in jail and had his career irreparably damaged.

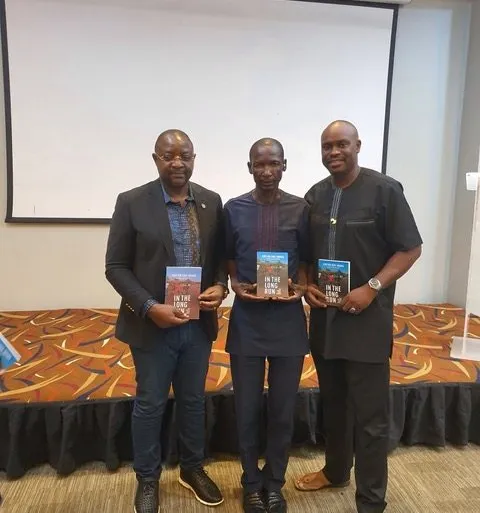

This episode is the subject of, In The Long Run – The Great Race Fiasco, a recently published book by former Nigerian quarter-miler Enefiok Udo-Obong.

The 2000 Olympic gold medallist interviewed key players and witnesses and followed a trail of newspaper reports and legal documentation to tell what he says is a remarkable but little-known story of sporting injustice.

“He was an icon and a shining star, but that episode dimmed his glow,” Udo-Obong told Al Jazeera.

“It didn’t just [destroy] Gideon, it killed the future of a lot of young ones who were looking up to him. They all saw what happened to someone who they saw as a hero, who they saw as a champion; how he ended up.”

‘Joy turned to sadness’

Hagack was born in 1971 in Tuwan Kabwir in Pankshin, part of the mountainous Plateau State in central Nigeria.

His athletic potential was already obvious in primary school. It was only after completing vocational skills training in 1991 that Haggak began to run full-time on the national stage, recording impressive finishes in various competitions across the country over distances between five kilometres and 30km, and later representing his country abroad.

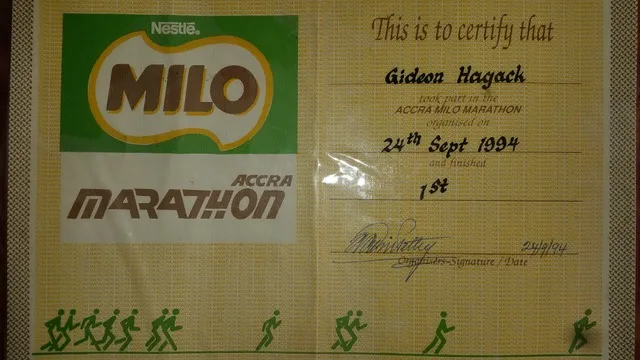

He was selected to represent Nigeria at the International Milo Marathon in Ghana on September 24, 1994. He won, prompting great fanfare back home and igniting dreams of winning the world’s major marathons.

Competing in the Lagos event so soon after was a stretch physically, but with a record $4,500 prize money on the line, and buoyed by the confidence of his exploits in Accra, Haggak decided to race.But his unexpected victory may have presented an unwanted headache for the race’s organisers.

Nigeria does not have a rich history in distance running; much of its athletic pedigree is in sprinting, while East African nations, such as Kenya and Ethiopia, have tended to dominate in marathons.

In a bid to make the Lagos race as prestigious as possible, the organisers had incurred significant expense to invite top international marathoners, many from East Africa.

It is Udo-Obong’s theory, outlined in the book, that a local winner may have led the sponsors to question the credibility of the race. Amid Hagack’s celebrations and a media scrum, the theory that he must have cheated took hold and reached the ear of the special guest of honour, Lagos State’s military governor, Olagunsoye Oyinlola.

Hagack was whisked away to what he initially assumed was a private reception at Government House. After waiting there for six hours, shivering and famished in his drenched running garb, he was accused of cheating and his immediate detention was ordered by the governor.

“It was a very sad and horrible experience,” Hagack told Al Jazeera.

“The joy of winning quickly turned to sadness. I went from a successful athlete to one locked up with criminals because some people couldn’t believe it was possible to win an international marathon. Imagine sleeping next to criminals in prison, going to court for something I knew nothing about and being treated like a criminal for being successful.”

After being held in jail for five days and denied access to a meeting with a lawyer, Hagack was pressured to admit guilt on threat of a lengthy incarceration, but was told that a guilty plea and apology in court might see him set free. At the magistrate’s court, he nevertheless pleaded “not guilty” and was granted bail for being a first-time “offender”.

Yet, despite the AFN’s insistence of malfeasance, not only was there no formal complaint made by Muriuki against the outcome but there was no consensus over how Hagack was supposed to have cheated.

In his report following the race, the technical director of the Athletics Federation of Nigeria (AFN), Rotimi Obajimi, claimed that Hagack “unexpectedly joined” the leading runner Muriuki, who he insisted had established an insurmountable 500-metre lead over the rest of the field, in the National Stadium.

“I remember this incident vividly, because within the stadium complex, Hagack emerged from nowhere to join the race and we had video evidence from NTA [Nigerian state TV] to back it up,” Obajimi told Al Jazeera.

“This was an international marathon and athletics’ global body IAAF concurred with our findings. It’s sad that some of the top AFN officials are no more because we did the right thing.” In fact, at five random checkpoints along the race route, bands were handed out to the contestants, and Hagack had collected all five of them.

Following the formation of an independent panel of sport administrators that placed the burden of proof on the accusers, the AFN were subsequently unable to prove their case and Hagack was officially exonerated by the panel in early November 1994.

The court case against him was subsequently withdrawn and an out-of-court settlement was reached.

Asked about the saga and his decision to order the arrest of Hagack, Oyinlola, now 72, told Al Jazeera, “It’s almost 30 years now and I honestly have no recollection of this particular incident.”

However, Hagack has still not received his prize money nor the agreed compensation. His state-appointed lawyer, Danjuma Tyoden, did however receive the sum of 370,000 naira (about $16,600 at the time) – 100,000 ($4,500) as prize money, and 270,000 ($12,100) as compensation – from the sport ministry in late 1996.

Tyoden told Al Jazeera that he has never actually met Hagack in person to this day, despite repeated attempts to do so on his part.

He claimed that, when it came to getting the compensation to Hagack, he reached out to the Plateau State director of sports, who “brought out a paper and started listing how the money was going to be shared to the commissioner, the permanent secretary at the ministry, the director overseeing sports matters, the chairman of the sports council, etc. He didn’t even mention Gideon Hagack”.

As a result, he decided to hold on to the received sum, but maintains he is willing to hand it over at the earliest opportunity.

But Hagack has denied Tyoden has made an effort to give him the money.

“I was also hoping to meet him at the book launch, but he did not show up. For honesty, decency and sincerity, at least I deserved the prize money he is holding,” he said.

‘The truth gets to be heard’

Although he had been exonerated, with a cloud hanging over him and his loss of trust in the system, the marathoner’s career was effectively over and the Lagos marathon was his last competitive race.

“Mentally and physically, I never recovered from that horrible experience,” he said. “My biggest satisfaction was to finally be cleared [by the panel] but the damage stays forever. My family name will not be connected to cheating: that is the most important thing for me.”

Now married with six children, Hagack works for the Plateau State sports council, training young athletes and leading an existence away from the public eye.

“I couldn’t let what stopped me blocked others from fulfilling their own dreams,” he explained.

Udo-Obong said there is no telling what Hagack could have gone on to achieve and that he was driven to write his book because he identified strongly with the injustice Hagack suffered: The 2000 Olympics gold medal in the 4×400-metre relay was awarded to Nigeria retrospectively in 2012 after a member of the USA quartet admitted to using performance-enhancing drugs.

“[I] was denied the elation and the once-in-a-lifetime experience of having my national anthem sung to me in front of millions of people,” Udo-Obong said.

While the sheer callousness of the treatment Hagack received startled Udo-Obong, most regrettable for him was the death of a champion’s aspirations.

“[Hagack] was imprisoned for winning,” he said. “He tried to climb up the ladder and they killed his career.”

Yet, Hagack was grinning from ear to ear at the book launch in April this year.

“I am happy to see this book because, finally, the truth gets the chance to be heard,” he said.

“[The book] serves as a significant reminder of how the people who should lift you up could end up taking you down.”

Originally published in Aljazeera 22 Jul 2023