This corruption crusade is at the crucial jucture of a needed change in mindset, towards social transformation.

This critical gap in relating the burden with the cause, through a very popular process of engagement, is possibly the one of the most significant value additions that the Akin Fadeyi Foundation (AFF) has brought to bear on the series of anti-corruption advocacies it has engaged in, over the past half a decade.

If there appears to be a key reason why many efforts at containing corruption in Nigeria have had less than optimal impacts, this seems largely apparent in the nature of the methodology usually adopted, which customarily tends to operate in a top to bottom mode. Whether in terms of the creation of policies and institutions that seek to corral the people into a notion of restraint, or the manners in which the endeavours are ‘sold’ to citizens, there has always been that palpable lag between the design and its outcomes.

A better proven approach has been one inclined to reach out to the people in a bottom to top manner, persuading and convincing in the evidence it shows up, on the need for societal change, both in the perceptions about the problem and its associated behaviours. This becomes particularly instructive, for instance, when the costs and impacts of corruption are highlighted in terms of how they affect and disrupt our daily lives; depicting the strong link between the material opulence of political office holders and the lack of drugs or personnel in our hospitals. Or how the votes we have collected tokens for are connected to why public education has to be without classrooms, textbooks or other learning aids.

This critical gap in relating the burden with the cause, through a very popular process of engagement, is possibly the one of the most significant value additions that the Akin Fadeyi Foundation (AFF) has brought to bear on the series of anti-corruption advocacies it has engaged in, over the past half a decade. It creates easily relatable vignettes of modern living (either though the one-minute drama skits, the radio or TV narratives) that not only needle, incite reconsideration of the acts of corruption and then personal contrition/behavioural catharsis, but become composites of encounters that impel a sense of ‘ownership’ of the transformative experience in its audience.

This methodology, hinged to an effective behaviour change advocacy has been highly successful in the way it connects very easily to people in their local and private spaces, were it takes the anti-corruption message to them, utilising a host of popular figures in the Nigerian entertainment industry – actors, actresses, and show business personalities – as arrowheads of information, and change agents. Akin Fadeyi Foundation took the battle for behavioural change to the individual level; directly to the ‘I’ who needs to change across multiple locations, in order to build a critical mass for social change. This approach gained enormous traction in the past three years, with the support given to the engagement by the MacArthur Foundation.

And, the numbers are quite staggering, if not exhilarating – reaching an estimated 100 million people with its anti-corruption messages across various nodes of the national and international broadcast media; from television to radio and then the social media! A vital segment of the demographic of outreach comprised youths of the working age (between the ages of 15 and 35), extending up to 70 million overall, and considered a principal target of the messaging.

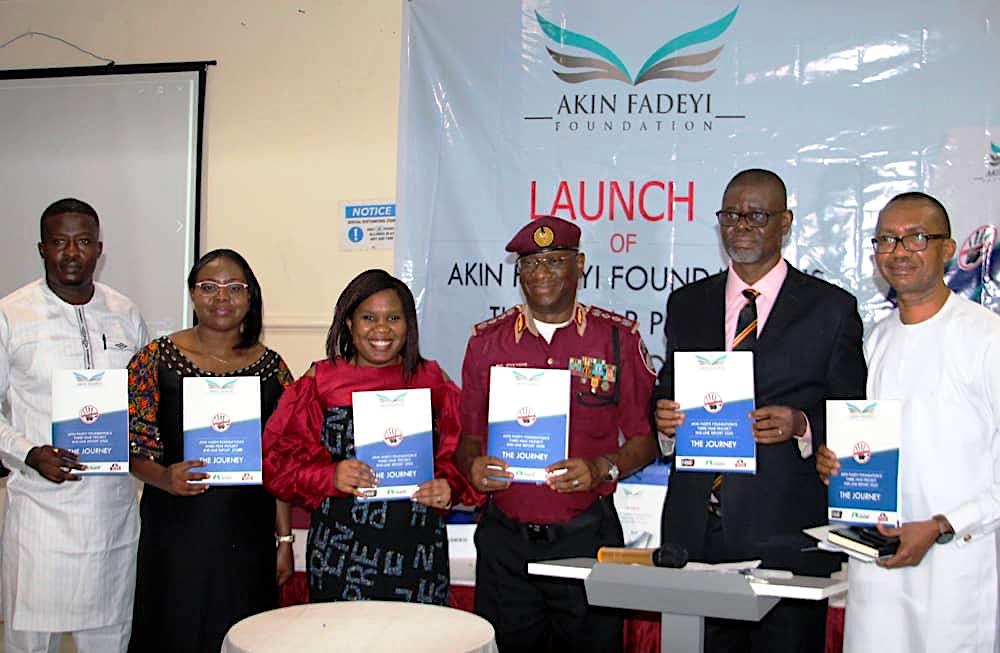

In the recent report of the Foundation, presented publicly on July 13, “The Journey” embarked upon by AFF in the past five+ years, even while essentially chronicling the high moment of the past three years, unveiled the extent, alongside impact of the Foundation’s anti-corruption programming, principally through the audio-visual campaign tagged, “Corruption: Not In My Country”.

Through this intervention, the offering had included the production of 60 Corruption Not-In-My-Country drama skits, coupled with 21 episodes of the “Never Again” radio drama, and nine episodes of the “Badt Guys” – a television series that ran for nine weeks. And, the building of a technology platform for the reporting of corruption, the FlagIt app, which has more so gotten its remit expanded to enable the documentation of sexual crimes in society. Still, there was the additional capacity building held on the sensitisation against corruption for over 500 students, in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja.

The Akin Fadeyi Foundation crusade against corruption is of very critical relevance to Nigeria at this historical juncture that the menace has risen to unprecedented or exospheric levels, and in which citizens not already enmeshed in the social ill are merely time-bidders, waiting for their opportunities for participation. Hence, the highly crucial need for the change in mindset as a collective responsibility…

Equally terrifying are the numbers that the Akin Fadeyi Foundation’s public advocacy drive has been warring against. Corruption has become one of the most insidious facts of Nigeria’s post-Independence existence, accounting for the trajectory of arrested development of a country of great human and material resources that has constantly punched far beneath its weight, due to the relentless haemorrhaging of these resources. As such, it has not only evinced some of the worst indices on the Human Development Index, also in 2012, Nigeria is said to have lost over $400 billion to corruption since Independence in 1960. At this point, almost a decade after, the figure is projected to have gone north of $500 billion.

The depth of the burden of corruption in the country has revealed in its constantly being rated as one of the worst manifestations of the social ill in the world, ranking 144th out of 180 countries measured by Transparency International (TI)’s Corruption Perception Index.

Much of the incidence of poverty – ranging from its more benign hues to its extreme form of expression – and immiseration are as much the indication of pervasive corruption in the country, as they are the outcomes of poor policy and planning, with the former reinforcing the latter, and vice-versa, in a continuous concentric interplay. In the present, the fallouts of this is revealed in the over 10 million out-of-school children in the country, which is the highest in the world; a poverty headcount rate of 40 per cent, having over 90 per cent of citizens locked up in dirt scarcity – 60 per cent of who are women. Also, while more than 40 million women of childbearing age neither have access to proper healthcare nor adequate nutrition, this has led to health issues in childbirth, and more than 10 per cent of the global maternal mortality, among similar gory statistics.

No doubt, corruption is one of the great social menaces of the times we live in, with its global cost being put at no less than $2.6 trillion or five per cent of the global GDP, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). Because states and governments have been stripped of their capacity for social provisioning due to the deleterious ravages of corruption, this has yielded space to conflict, terrorism and cognate forms of instability, occurring in tandem with the illicit traffic in drugs, arms and people, etc.

The Akin Fadeyi Foundation crusade against corruption is of very critical relevance to Nigeria at this historical juncture that the menace has risen to unprecedented or exospheric levels, and in which citizens not already enmeshed in the social ill are merely time-bidders, waiting for their opportunities for participation. Hence, the highly crucial need for the change in mindset as a collective responsibility, towards the transformation of society.

An important part of the AFF public advocacy strategy was the mobilisation of what it describes as a “citizen-led societal transformation” activated through a Corruption Prevention Approach and the tackling of corruption in the department and agencies of government through a Corruption Fighting Approach. The latter necessitated a major engagement with public institutions such as the Nigeria Police Force, the Federal Roads Safety Commission (a central agency for the operation of its technological anti-corruption platform, the FlagIt app), the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission, Nigerian Immigration Service, and ministries, departments and agencies of government, etc.

It was deeply pleasing to learn that the AFF avails itself of some of the best practices in the social enterprise, such as its subscription to the Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) protocol – which actively enables the affirmation of women, children, person with disabilities and other marginalised groups – in its processes and operations. It claims the intentionality of this approach in its work, hence the different sensitivities it brings to bear on its programming and projects.

As a very modern outlook to the attainment of social change, invariably resolving in advancement, it is remarkably how the Akin Fadeyi Foundation strongly considers the issue of collaboration and partnerships, in which the collectively achieved is sturdier and more resilient than the individual parts.

In this regard, the audio-visual advocacy materials it produces are carefully scripted to avoid language that could trigger gender bias, while the cast and crew of its productions ensure gender and social inclusion, and the Foundation has up to 55 per cent of female representation in its team. For AFF, “building a gender-inclusive workplace does not end with hiring more women or emphasizing pay equity, we have also built a system that supports and encourages women-led teams.”

As a very modern outlook to the attainment of social change, invariably resolving in advancement, it is remarkably how the Akin Fadeyi Foundation strongly considers the issue of collaboration and partnerships, in which the collectively achieved is sturdier and more resilient than its individual parts. According to the AFF report, this operated on a number of levels, both lateral and vertically to achieve all it has done so far with the “Corruption: Not In Country” project.

In this regard, there were the different partnerships with private and public sector institutions, also including the National Orientation Agency, the Federal Ministries of Women Affairs and Health, the Public Complaints Department of the Nigerian Police Force; and equally, the Afe Babalola and Elizade Universities. Being largely media-driven, the AFF-driven public advocacy programme benefitted from collaborations with organisations such as Nigerian Television Authority (NTA), Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN), Television Continental (TVC), RSTV Port Harcourt and Channels Television, etc., who were not only believers in but major propagators of the message. Moreover, the skits were aired on CNN, Africa Magic Epic, Africa Magic Family, Super Sports 3, and Mnet Movies digital television channels. Among the national newspapers, there were active partnerships across the legacy and online press, from Vanguard, to Daily Sun, Premium Times and The Cable, each affirming and reinforcing the unique social change advocacy of the AFF messaging.

Yet, with all the important milestones traversed in the “Corruption: Not In My Country” programme, the AFF report intimates on a number of challenges encountered all through the interlinked series of projects, from the difficulty in securing the ‘buy in’ and collaboration of governmental stakeholders, to other levels of institutional pushbacks, coupled with the shortness of timelines, in relation to the delivery of better outcomes.

Significantly, there were associated risks, especially with the deployment of the FlagIt app in going after criminally minded citizens who sought to wreak havoc through their unusual corrupt dealings, including the sextortion of fellow citizens. Added to this was the repeated head butting with the Nigerian Police, whose corruption-infestation evolved in routine lawlessness against citizens, which occasionally resulted in unwarranted deaths. Still, all this was presented as a journey that was as remarkable in its trajectories, as it was nerve-wracking.

In the Akin Fadeyi Foundation’s “The Journey” report, what could possibly be deemed as the most reverberative of acclaims was given to the support of the MacArthur Foundation to the “Corruption: Not In My Country” project. This had packed a huge punch that gave major fillip to the earlier instances of funding by organisations like the European Development Fund, in its concert with UNODC and UNDP, through with much of the illustrious work being reviewed were made possible. Hence, the resounding chorus of gratitude was offered by AFF, not only to the On Nigeria programme of the MacArthur Foundation, but also to its seasoned leadership, comprising such change administrators like Dr Kole Shettima, Erin Sines, Dayo Olaide, Amina Salihu, and their other noteworthy colleagues.

With the uncommon industry exhibited by AFF in its social crusade against the monster of corruption in the past three years, it becomes easier – with a deepening of this process – to dream of a future in which most Nigerians will be able to say, with all sense of conviction, that: “Corruption: Not in my country!”

Ololade Bamidele is the Secretary of the Editorial Board of PREMIUM TIMES.