Abraham Lincoln knew great loss and deep sorrow throughout his life, and it may be that his lifelong melancholia gave him the strength to handle the crises of his years as president.

By Elizabeth Sherril

It was my grandfather who gave me a lifelong love of Abraham Lincoln, one that was to help me in a way he could never have imagined. As a boy of seven, Grandfather had seen the funeral train carrying Lincoln’s body home to Springfield, Illinois. From that moment, sobbing by the tracks, he’d taken Lincoln as the model for his own life of battling injustice.

I was seven when Grandfather gave me my first book about Lincoln. In Abraham Lincoln, the Backwoods Boy, I read about the son of a near-illiterate farmer, walking miles through the snow to borrow a book. Straining his eyes to read by firelight because he had to work in the fields in the daytime. Starting to write and getting whipped when his father caught him “scribbling” instead of feeding the pigs. Lincoln went right on writing. This determined boy became my model too. I started writing, and when I had to stop to set the dinner table I was sure Lincoln would have understood my feelings

At eight, I went to a new school. I remember going for the first time to its library, much bigger than the one in my old school, with quiet signs on the tables and portraits on the walls. Over the librarian’s desk was a color photograph of the president, Franklin Roosevelt, seated at his desk. On the right wall was a painting of George Washington standing by a cannon; on the left was one of Thomas Jefferson, holding the Declaration of Independence.

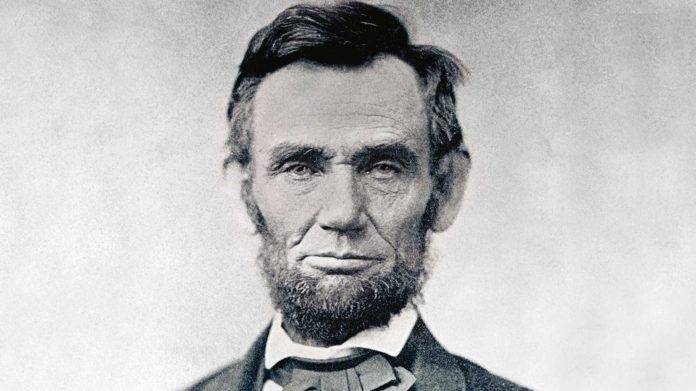

But it was the picture over the door, when I turned to leave with my new library card, that stopped me. It was a photograph, this one blackand-white: a tall, thin man with his hand on a table and with the saddest, most pain-filled face I’d ever seen. The gold letters on the frame said Abraham Lincoln. It couldn’t be! Lincoln, my brave hero, who won every wrestling match? The ragged boy who told such funny stories that crowds would gather to listen? They’d put the wrong name on the photograph

“Friendless, uneducated and penniless,” Lincoln left the family farm to strike out on his own in Illinois. That this disadvantaged young man was able to carve out a career for himself as a lawyer seems marvel enough. The fact that he did it while carrying the burden of depression was what astonished me. Lincoln was a sad, gloomy man, a man of sorrow.”

But of course it was Lincoln, and over time that portrait made him more important to me than ever. Already I was experiencing the bouts of depression that, three years later, would lead my parents to the then-rare step of taking me to a psychiatrist. Despite her help, I continued to have (and still do) occasional descents into those bottomless depths. And at these times, my model continued to be Abraham Lincoln.

My depression had no discernible cause. His had many. The death of an infant brother was not unusual for those times. But his mother’s death was as traumatic an experience as any nine-year-old could have. In the family’s one room cabin, there was no escaping her agonies from milk sickness, a disease then ravaging their Indiana frontier community. People who ingested milk or meat from cows that had fed on the white snakeroot plant suffered uncontrollable shaking, hideous stomach pains, continuous retching. For a week, Lincoln’s mother tossed in torture on her bed, her tongue turned black, unable even to speak words of farewell.

Abraham had one surviving sibling, a brilliant sister named Sarah who was two years older and his closest companion. Abe was 18 when Sarah gave birth to a stillborn child and died.

At 22 and, in his own words, “friendless, uneducated and penniless,” Lincoln left the family farm to strike out on his own in Illinois. That this disadvantaged young man was able to carve out a career for himself as a lawyer seems marvel enough. The fact that he did it while carrying the burden of depression was what astonished me. “Lincoln was a sad, gloomy man, a man of sorrow,” his long-time friend and law partner said, noting once that “his melancholy dripped from him as he walked.”

Even after his successful run for a seat in the Illinois state legislature, his sense of dejection did not lift. When a bill he’d worked for was defeated, he wrote to a friend, “I am finished forever.” How familiar I was with this I’ve-failed-and-nowit’s-hopeless feeling! And yet…as despairing as he felt, Lincoln somehow managed to succeed in every way that mattered. It wasn’t that his depression went away. An artist working at the White House in the final year of Lincoln’s life remembered that “Mr. Lincoln had the saddest face I ever attempted to paint.” By my own late twenties, when my depression became incapacitating, reading about Lincoln’s life was a pathway back to the functioning world. Sometimes all I could do was stare at a photograph of his downcast face. Yet in the strange psychology of depression, this cheered me. If Lincoln could accomplish so much while feeling so bad, surely I could get up and do a little.

It was not until many years later that I began to see something even more life-giving in Lincoln’s story. Many times in accounts of his life, I’d noticed references to his melancholia. Now I came upon the defi- nition of that word as used in the 19th century: fear and sadness without apparent cause.

Without cause? But Lincoln had so many reasons to be depressed! They’d only multiplied throughout his life, culminating in the death of his two little sons and the terrible slaughter of the Civil War. But his melancholia suggested something more, something closer to the medical condition recognized today as clinical, or persistent, irrational depression.

It’s only in the last few years that researchers have delved into this aspect of Lincoln’s life. A family history of depression, “the Lincoln horrors.” Lincoln’s own conviction that he was constitutionally subject to melancholy, which he dubbed “my peculiar misfortune.” His frequent talk of suicide— there was a period when he didn’t dare carry a pocketknife for fear of using it to kill himself. Two major breakdowns, the first in his mid-twenties (the typical onset age for unipolar depression in men), the second in his early thirties.

“If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would be not one happy face upon the earth.”

“I am now the most miserable man living,” he wrote at age 32. “If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would be not one happy face upon the earth.” Concerned friends removed razors from his room, mounted a suicide watch and feared for his sanity. In an effort to escape his misery, Lincoln underwent the standard medical treatment of the times—a weeklong torment that would have included starving, bleeding, dunking in icy wa- ter, purging with black pepper drinks, swallowing mercury, applying mus- tard rubs that burned the skin raw. He emerged emaciated, exhausted and, unsurprisingly, feeling worse than ever. Today’s medicine offers effective drugs and skilled counseling. If these methods had been available then, Lincoln might have been a less sad and tormented person.

But would he have been as great? Here is the life-giving new insight Lincoln is bringing me. Many researchers today, looking afresh at Lincoln’s melancholia, are grateful that he was not “cured.” From his chronic depression may have come the coping skills, the realism, the wisdom that steered the nation through its greatest crisis. What strengths may depression have bestowed on our greatest president?

Humor.

Jokes and storytelling were Lincoln’s lifelong refuge from despair. As the casualty figures in the war mounted, grief threatened to overwhelm him. Far from a sign of callousness, his humor helped him bear the horrors he felt so deeply. “I laugh,” Lincoln told a disapproving member of his cabinet, “because I must not weep.”

Humility.

He had the modesty of a man continually aware of his own defects. In an age of swaggerers, this highest official in the land called himself “a man without a name.” Knowing his own failings, he could forgive those of others. As Northern leaders called for continual retribution from the defeated South, Lincoln appealed for “malice toward none.

” Dedication to a great cause. It was the issue of slavery that pulled Lincoln back from the brink of suicide. Despairing of himself, he determined instead to devote his life to others. Dependence on God. “I am driven to my knees,” he said, “by the conviction that I have nowhere else to go.” He saw himself not as captain of the ship but as the humble helmsman, striving to steer as the true Captain directed.

Humor, humility, service to others, faith—these are qualities, I think, that all of us aim at. That it was not despite his depression, but in part because of it, that Lincoln’s character developed as it did—this is the wondrous promise he holds out to people like me. His arena was a national one, mine one of family and neighbors. But the fact that God can use the negatives of our lives, even the blackness of depression, to shape us to his purposes—this is good news indeed!