The body. The birthplace of meaning and speech, of fear and desire, longing and loathing, of silence and the expression of silence. The body, ‘the ground for all experienced values, for both intimacy and alienation, freedom and limitation.’ The fleshy materiality that can withstand the storm and embrace a thousand blows and lesions and be taken from the world and then be returned to it with traces of trauma in place of memory. The body. Unconsciously re-performing invented traditions in order to reduce them to a singular grammar that awaits liberation from the silence of historical violence. The body’s surface tension is marked by the blood-curdling act of military adventurism. The body, remembering the seared bullet holes, the scattered limbs, kwashiorkor bellies, the disembowelled pregnancies and toxic blood that drains life of all meaning. It is here, on a darkling plain of ineffable violence that the fragmenting of psyche and soma commences.

And yet. Our indebtedness to orthodox Western philosophical thought would have it that the body is mere meat that produces life, rather than that which brings the world into being. Embodied being is reduced to a biological conundrum, divorced from all mindfulness. The metaphysical violation of embodiment mirrors the body in conflict, in terror. A body is all too readily expunged of its vitality through attacks and combat. The reality of millions of flesh and bones ‘charred to ashes, charred black’ in narration is a reminder that an horror has taken place on bodies and thus, completes the cycle of betrayal and provocation of future anxiety and distrust as the body recalls the silence of others as ‘people were hounded out of their homes’ . Any life, in the blink of an eye, can be subject to the machete, to bullets and bombs, or piercing knives that inscribe the tattoo of victory on the bodies of the vanquished. Just as any embodied life, reduced by metaphysics to a mind in a body, is scarred by the very conceptualisation. Such embodied motility carrying the living body of tradition is reduced to the anonymity of sacrifice required in order to secede from the fiction of the nation and retreat into an imaginary shared ethnicity. Retreat and the creation of a timeless ethnicity are close to inevitable for traumatised and wounded bodies. The physical body is a condensation and congealment of the world, bearing the imprint of culture and history. The body absorbs and interiorises both physical pain and cultural artefacts , demonstrating that “the earth has been a lunatic asylum for too long”.

Through the body, we come to experience pain and joy. Extreme mental-emotional states such as ecstasy and suffering, make little sense without the facticity of embodiment. ‘Emotion is precisely the experience of embodied sociality’ . The body dancing in pain is a perpetually unfolding body, always on the verge of “homeopathic laughter”. But the body cannot heal when the wound is still so fresh and without monuments, memory icons or discursive engagement in the body politics. The body’s arc of traumatised movement thus strives to create a singular metaphorical community, inventing and defending a collective self, yearning to create solid identities, common legacies and attachments in place of liquid ethnicities, difference and rupture; longing for a place of origin and for fertility nursed by the need for heterosexual marriage and continuity. A plurality of ethnicities and regional differences that war has reduced to the singular. The desiring body of therapeutic ethnic loyalty promises to return the scattered community to the rule of the father, whose virility war has diminished. The wounded patriarch’s virility must be re-established and asserted through the body of women’s reproductive value in order to reaffirm the proprietorial power of heterosexual masculinity.

The Middle Passage. Bodies squeezed into forgetting as they are rocked from side to side across the Atlantic. And in that forced forgetting, everything is and must be remembered. The embodied being retains and sometimes stutters to recall, in ‘a communication more ancient than thought’. No matter how extreme the event, when the mind hastens to forget, the body stores the experience. This insight is at the root of all forms of therapy: the organising principle of returning the mind to an encounter with the trauma, stored somewhere within or on the body. The trauma silently urges new narratives, which rely on both the imaginative retrieval of creative workers and the real life retelling. Proximity to and distance from the primal scene generates its own form of narration, which tries to commemorate the minutiae of the horror as though to hold it up to time. Distance can produce “an unbiased, total assessment of the whole tragedy” even as it can make forgiveness difficult because a renewed anger is reborn by each new generation demanding explanation and resolution.

Beyond basic phenomenology and pyschoanalysis, we must recall Elaine Scarry’s monumental book, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of a World (1987). Scarry alerts us to the relationship between physical pain and silence. The tortured body loses its sense of world and articulacy. The imprinting of pain onto the body leaves the subject in silence, resisting linguistic objectification. Quietness envelops the world of the subject of incarnated violence. The physical violence of war contradicts and contracts the world down to ‘the small circle of one’s immediate physical presence’ . No matter the retention of the trauma within the body, the subject can no longer speak. Imagine the body that must obey the excruciating pangs of the moon’s flowing call while bombs fall; the body exposed to the agony of rape and unwelcomed pregnancy; the body that is so hungry that it boiled and ate the leather floor rug until it became sick. Violence on the body is world destroying, returning it to the primal scream anterior to language, meaning and agency.

But we must recall the blows the body withstands and we must move out of incarnated silence and move towards language to access what Lawerence Langer calls the “ruins of memory” . Scarry also alerts us to a pathway for the body in pain. Resistance to silence emerges through creativity, making and fabrication, through the work of the hands, against debased forms of power and ruination. The fingers re-member old tunes on the piano; fingers grip the handle bar of the bicycle and re-attune the body to forgotten movements; the fingers use the “black alphabet and black typeface […] to articulate the memory and the image of unspeakable acts and events”. The body must return to language to capture and conjure up the spirit of dance amidst the chaos of existence. It is the body’s creative being that can hasten an end to muteness and the birth of expression. Hence: the black body and dance and the return to poetry and cultural artefacts time and time again in limit situations.

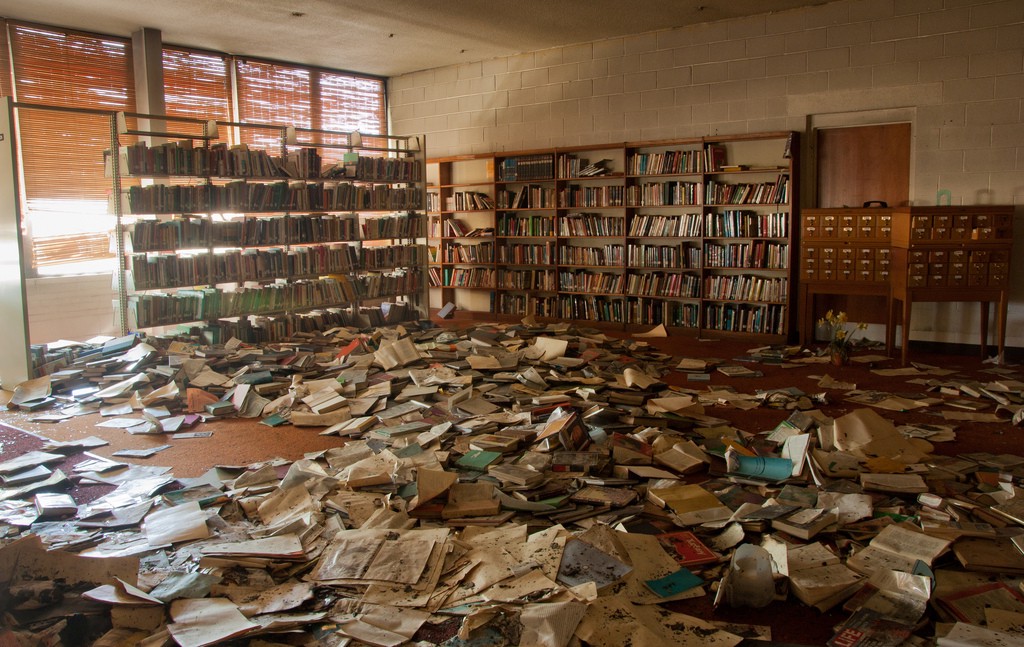

And so we return to Biafra. Not through the personal recollections of ordinary, untutored survivors, but the articulated, politicised voice of writers and artists. We are still waiting as time passes and memory slowly recedes into a wordless abyss. The silent war Nigeria made with itself from May 1967 to January 1970; the war against historiography and memory. Over a million Biafrans died of strategic starvation, disease, fighting and more. We Nigerians scarcely talk of it. There is an active forgetting at work: a use and abuse of history for life, the control of memory as a tool of political power. It is not so much dust swept under the carpet, as: there is no carpet; there is no more dust. And there is no longer even any floor to the experience. Yet, ‘we can touch history’ as memories stare at us demanding to have their say.

Conversations about Biafra take place as gaps in conversation, most often in south-eastern living rooms and in hushed tones of somatic ressentiment across the Igbo diaspora. The conversations are grammatically constructed around silence: the ineffable taboo of the national consciousness. It has been little more than a handful of writers who have tried to assemble a language to the experience. Still, the story is yet untold. Much of the documentary evidence we have on Biafra can be gleaned most vividly through literary works and memoire — Sunset in Biafra, Sunset at Dawn, The Man Died, Never Again, Destination Biafra, Season of Anomy, Toads of War, The Seed Yams Have Been Eaten and Half of a Yellow Sun. Mostly by Igbo writers, but there are some by men of other ethnicities. But a deafening silence from women on the other side, the Nigerian side. There is an almost complete absence of first hand accounts from ordinary survivors. Accounts not just of horror and carnage, but also of moments of laughter and humour, of birth and marriage amidst the most indelible devastation known to Nigeria’s modern history. There is much work to be done as memory fast recedes.

We need life stories from the Nigeria side that are not the adventures of military men. And even more from the survivors and from their children. When Biafran women were menstruating under the ever-present threat of rape, and Biafran patriarchs rejected raped daughters, wives and mothers, what was happening to Nigerian women across the Niger River? Did they allow themselves a moment of awareness, of double consciousness, of empathy? What psychic anxiety were women experiencing with the knowledge that their pregnancy could be disembowelled by crazed machete soldiers at the next road block? How does rape and sexual violation destroy bonds of loyalty and ‘friendship that had existed between former neighbours’? What stories were women on both the Nigerian and Biafran sides telling each other? What narratives are there children formulating, fomenting and fermenting? Can measuring time melt the sense of betrayal and mistrust that the silence of the Other provokes between and among women, from Biafra to Nigeria? Is history fashioned out of the ruins of memory merely monumental, antiquarian or critical? Where are the ethnographers, historians, sociologists and filmmakers collecting and recording life stories of every day people’s experience and memories?

We must listen to the accounts of ordinary men and women who experienced the war. In the absence of an archive of eyewitness accounts, fictionalised accounts and memoirs are important because they provide emotional intelligibility and offer an initial means of “working through”. However, the need for life stories remains important for this bloody era. These accounts will help us to focus our minds on the small details of existence and those who lived through the war survived it and try to well in their soul in the present. In relation to women, life stories will complicate the role of women in the narration of the Biafran genocide: women as perpetrators, collaborators and victims alike, thus, these stories will puncture the simplifying “victim logic” of the defenceless female.

There is a huge lacuna at the heart of Biafra studies. A thousand questions demanding answers and stories requesting further exploration and probing. The stories lie below the threshold of consciousness, resting under many thousands of tongues. The stories also, of course, lay buried underground. Traumas turning to earth, which only the trees can now remember.

Perhaps then, this is Scarry’s point, written into the language of Biafra and echoed in Wittingestein’s statement “Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must be silent”. We must call upon writers to continue to write stories, to continue examine the archaeology of memory and rewrite the text of past wounds for the benefit of today. All we have is the balm of narrative, soothing the open wound of traumatised experience. The story becomes a form of suture: a stitch that heals experience, or at least begins the work of healing. For now, perhaps, invented stories, as invented traditions are the only effective means to ingest the poison of the past. But in this case, with mostly creative fiction, the horror of Biafra must still be encountered as a form of collective silence. Bodies, still numb with pain, are still not able to speak. The fathers of the nation have silenced speech in the country’s narrative. The mind has not been allowed to restore its relation to the body, by recovering the site of traumatic memory. There is a perpetual unease and silence.

But the silence runs yet deeper. The Nigerian civil war is not even part of the school curriculum. History has been banished to…. To where? It has not even been banished. There is no other place, where history may be found hiding. History has been dissolved, lime poured over bodies that forgot how to speak. Is it any wonder that participation and investment in the narration of Nigeria continues to elude many? The curriculum’s silence on Biafra cannot conceal the background noise of expectation. Many Igbos take the war to be incomplete, unfinished business. Rightly so. There has been no “national conversation”. No truth and no reconciliation. Just silence. The nation’s averted eyes in the face of another’s suffering mark the origin of contemporary acquiescence to militarised impunity, today’s excess-based injustice and judicial killings. Biafra was Africa’s first televised excursion into an African genocidal attack and the beginning of the drama of inertia and amnesia, and an enforced forgetting. While someone partied the night away with Courvoisier and Star Beer and the music of Tunde Nightingale, another died a slow and hidden death. Biafra was the birthplace of our loss of innocence and empathy; the residual shame that stalks our speech.

Our writers have started the process, but yet the process has not even begun. People are growing old. When will they start to speak and when will they start to re-remember? What stories will the unlettered eyewitness recounts provide? What will women say and what will they see as worth remembering and worth telling? What will they leave out and consign to the waste heap of history? The Biafra story is the incomplete story of the Nigerian nation and the suspension of resolution. Biafra was the beginning of our acceptance to live with the normalisation of violence and fear, which continues with the terrorist movements of our contemporary.

The words of the ordinary men and women who experienced Biafra must be brought out of the archive of silence. The archive must be made to speak the hundreds of language of this variegated landscape called Nigeria. (Medium)

First published in African Identities, Vol. 10, No. 3, August 2012, 1–6