My point of departure is to suggest that while there is no doubt that alternatives are a necessary, and even an inevitable component, of any living political system, it is important that as scholars and practitioners, we strive also at all times to demystify them from the excessive air of drama and circumstance in which they tend to be wrapped in scholarly discourses. This is for the simple reason that alternatives exist and are mobilised everyday and at all levels as part of our experiences of governance. In other words, alternatives, understood generally as encompassing forward-looking vision and practice that depart from a dominant but problematic and/or contested norm, are an integral part of everyday politics – and, indeed, all spheres of human endeavour.

Although they are fired by an admixture of vision, passion, and necessity, and, in highly repressive political contexts, would require to be pursued with courage and sacrifice, alternatives are also played out simultaneously at multiple levels – micro, meso, and macro. Additionally, they are carried by different actors – big and small, formal and informal, and domestic and external. Alternatives also manifest and are played out in different spaces – local, national, and even global, and at various points in times. They are the underlying drivers of the dialectics of political change.

In their intersection within a polity, they may translate into revolutionary moments of political renewal that arrest our attention. However, in most instances, they are also pursued “silently” with no less significant consequences for overall governance. Whether expressed in macro-national revolutionary terms or carried out “silently” in various localised spaces, alternatives are an embodiment of the agency of the people in all their diversities.

In our highly justified desire for a radical transformation of politics and power in Africa, including Nigeria, we very often set our sights almost exclusively at forms and levels of engagement that capture mostly the dramatic and the revolutionary on a grand national scale. This slanted approach to the mapping of change dynamics has been reinforced in recent years by such dramatic events as the so-called Arab Spring that swept through parts of North Africa and the Middle East, producing gripping moments which were served to us directly in our homes by global television, including the spectacular toppling of long-running political dictatorships and power dynasties. I suggest that even at that, underlying these grand events are an array of ordinarily anonymous or nondescript local forces, such as the neigbourhood committees, professional associations, womens’ groups, and youth networks, that were either already quietly immersed in or became converted to the quest for political alternatives and alternative forms of politics.

If the quest for alternatives is integral to everyday life and everyday politics, rather than only expressing or manifesting itself in dramatic moments of revolutionary change, then it seems to me that the strategic approaches we take to governance and the questions we ask must necessarily be different. This was a key consideration that fired my interest in the 1990s as we Nigerians pondered the issue of how best to overcome the prolonged scourge of military rule that had become a threat to national cohesion and continuity, apart from its many other failings. For me personally, as a civil society/social movement activist, that period was crunch time on how best to carry forward a struggle that had successfully hobbled continued military rule and opened up real prospects for a return to civilian rule and elected government.

Many of the Nigerians and students of Nigeria here will know that our country has a rich history of social movements with an impressive record of resistance against oppressive policies and rulership. However, there was always an historic challenge that faced the movement: How to convert resistance into power with which to push the alternatives around which militants were mobilised.

That same challenge was posed in the lead-up to the birth of the Fourth Republic: A social movement that was strong and organised enough to make a change in national governance impossible to avoid but not powerful enough to impose its alternative as the viable path for the country to follow. In part, this problem was reflective of the conception of change in the ranks of the movement as a totalising process that needed to happen on a macro-national and pan-Nigerian scale at the same time and all at once.

Let me quickly forestall a misunderstanding: Collective pan-Nigerian territorial change of the kind that will overturn a history of socio-economic underdevelopment and governance underperformance remains the historic duty of all those who seek the rebirth of our country and continent in unity, justice, peace, progress, and security. However, achieving this goal did not require an indefinite wait for the day when like-minded actors across the Niger would be able to create the national movement and momentum to translate opposition and resistance into national power. While the search for such a national change process was going on, it made eminent sense to seek to promote alternatives in various other sites where we could effectively already begin to make a difference. And this is exactly what some like-minded people like me and others decided to do in making the transition from civil society to political society.

As a frontline political party actor since 2005, a two-term governor, a two-term Chair of the Nigeria Governors’ Forum, and a Minister in the federal cabinet, I am able to state without equivocation that at different levels, in various domains, and through many mechanisms, it was possible – and valiant efforts were made – to promote localised alternatives in the political process and governance system. That these were localised did not make them any less necessary or significant; they impacted many and also set a new tone and tenor for politics, governance, and the interpretation of citizenship. Examples of such changes are many – and will be fully documented in due course – but I note here, for now, that in Ekiti State, to use that specific example, we were successful on several fronts in shifting the overall template of governance and resetting aspects of public administration.

Some of the changes we effected include: a) The restoration of a merit-based system of recruitment into the civil serve as we sought to rebuild state capacity and public administration; b) A raft of interventions to empower women, blunt gender discrimination, protect the girl child, and stem gender-based violence; c) the introduction of core social policies as a first step towards a new state-society compact – including a social security benefit system for the elderly; the institutionalisation of a state development plan, a system of public sector performance evaluation, and the curation of global good practices in the administration of public affairs; major investments in the restoration of values and ethics in everyday governance; efforts at restoring the civic culture in political competition; the adoption of a transition law aimed at strengthening continuity in governance and development despite administrative turnovers; the fostering of inter-generational engagements with a view to cementing a system of orderly succession, leadership recruitment, and mentorship, etc.

The initiatives taken were numerous and spanned various spheres of policy and governance. Inevitably, some required experimentation, adaptation, and innovation. Others were simply commonsensical or required us to learn from established good practices. In some cases, we registered immediate results. In others, expected results were slower in coming on account of ossified cultures that needed to be dissolved. Yet others are still work in progress. In all cases, they allowed us, within specific domains, sectors, and areas, as part of an overall strategy of change and progress, to demonstrate the feasibility of political alternatives and to practice alternative politics. Both endeavours were not without their challenges. Doing things, anything, differently ruffles feathers, high and low.

Many a stakeholder may be more invested in instant results as opposed to medium-to-long-term outcomes – remember the metaphor of “stomach infrastructure” as against physical infrastructure development. After years of failed promises, a cross section of the populace is steeped in cynicism about intentions. Assembling a team of loyal fellow travellers ready for the long haul has its own challenges. The import of all of the foregoing is that alternatives also have their own politics which must be played right for the changes in form and substance that are envisaged to have a chance of succeeding and making a difference. This fact immediately broaches upon the question of the strategy for change management that is adopted in a context in which the harvest is plentiful but the labourers are not only few, but even the ones available are poorly equipped and motivated. The would-be change maker is, therefore, also immediately confronted with critical issues of timing, phasing, and sequencing in the quest to drive an agenda of alternatives in policy, politics, and praxis.

I suggest that one of the difficulties that would-be change makers have had to deal with in the period since the birth of Nigeria’s Fourth Republic centres, inter alia, on the problem of timing, phasing, and sequencing.

I argue also that the politics of alternatives at any and every level requires alliance and coalition-building to undergird change processes. Furthermore, it will be foolhardy to assume that a ready-made and willing constituency for alternatives is in place in spite of the impression often created on social media; when crunch time arrives and the demands of change begun to be felt, the herd very often disperses amidst a crisis of expectations. Political and civic education must, therefore, go hand-in-hand with policies and leadership so that alternatives can find enduring anchorage in an organic constituency. For, even under the best of circumstances, active citizenship will need to be mobilised on an ongoing basis in order to sustain alternatives that negate established practices rooted in cronyism, maladministration, and various abuses.

In contextualising alternatives, it would be remiss of me not to make a few remarks on what is now being described as “alternative politics” or a “third force” in Nigeria’s contemporary electoral politics. The present context of electoral politics in Nigeria is dominated by citizens who are, for many reasons, disillusioned with mainstream political parties which they blame squarely for not delivering democracy dividends.

However, if alternative politics must be taken as a wholesale reform of our political system, and we are interested in the codification of a system of alternative politics that is consensual and developmental, then perhaps the argument to put forward, as a first step, is that our electoral system may need to be re-engineered away from the current majoritarian “winner takes all” model. Indeed, whichever political party wins the 2023 general elections, one can readily predict its going to be a close race. Imagining a race in which the eventual winner scales through with a 50.5 percent of the vote just as we recently witnessed in Kenya, it does not require a seer to predict that such an outcome is unlikely to enhance stability of the polity, let alone allow the militants of alternatives to thrive in our search for a national rebirth.

My sojourn in politics so far convinces me that any strategy for building sustainable democracy in a plural and divided society such as Nigeria must place a premium on electoral systems that will promote accommodation and inclusivity as a way of ensuring that the fractures and frictions that obstruct national change-making are blunted and dislodged. In the age of populism, elections help shape broader norms of political behaviour and we are already witnessing centrifugal, inter-ethnic and inter religious tensions as we move towards the 2023 elections. That is why as a first step, since we are unlikely to see any change in electoral reform before the election, my own view is that regardless of the outcome of the election, it would help if a national unity government is the eventual product, one that is consensus-driven with a clearly agreed agenda for broad-ranging reformation and transformation. This is especially so if the outcome of the election is not overwhelmingly definitive.

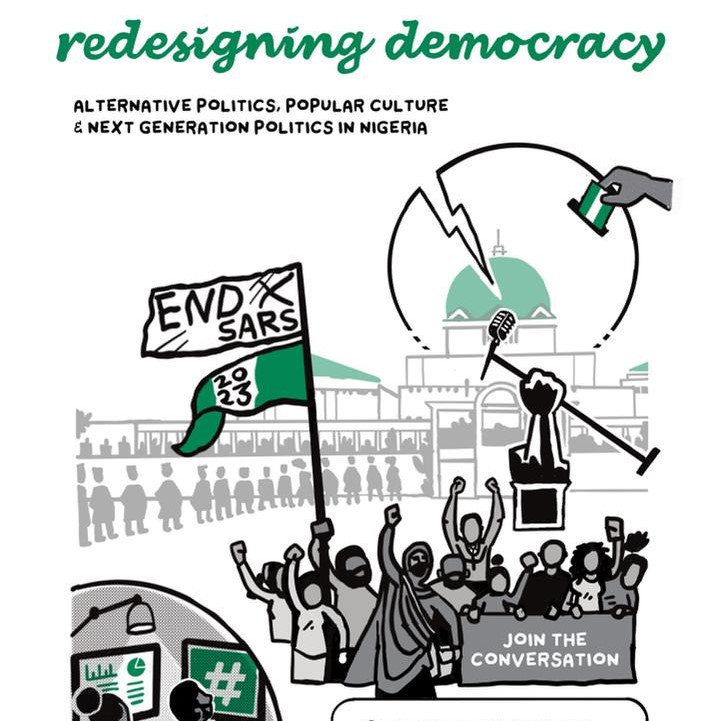

This is why I see the debate about political alternatives and alternative politics a superfluous one. Important as they are, the institutions of direct state power and electoralism are just the tip of the iceberg in the democratisation complex. Indeed, genuine democracy ought to rest on a much richer ecology of associational and organisational life and should be nourished and reproduced through every-day struggles of the citizens. But when we broadly define the everyday struggles as simply the handiwork of ‘civil society’ as in the EndSARS or Occupy Nigeria movements, we strip them bare of their spontaneity and deeper meaning and romanticise ‘civil society’ as the rationally ordered, codified and all-knowing alternative to government and overplay our abilities as activists to counter the inherent inequities of class and markets. Even worse, we are presented or we present ourselves as antidotes to the ills of democratisation, which is why single issue causes like EndSARS have been hugely successful in form but exaggerated in their expectations and eventual outcomes. The reason for this crisis of exaggerated expectation that activists suffer is not far-fetched. The truth is that as long as we live in the post-Westphalian world of sovereign states, we exaggerate the ability of the civil society to stand up to the power of the nation-state or the mega corporations on its own steam.

This is why I am not sure that the solution to the current deficit that our democracy is experiencing can be solved with posing activism as a counterpunch to politics. For autonomous institutions to play a different role in mediating citizens’ democratic choices, their organic development must be combined in a more nuanced manner and a more systematic way with the use of public and state power.

The choice is therefore simple: one can continue to snipe on the fringe and complain that government is not listening to the yearnings of the people. Alternatively, one can stop agonising about missed opportunities and organise in a manner that places citizens as drivers of change in our quest to restore communitarian values and a future of hope and possibilities for our people.

I have taken the pain of working us through the fact that the politics of alternatives occur at various levels in part because it allows for a more precise assessment of prospects for innovation and transformation in 2023 based on the lessons of experience. Here, the two final points I would like to emphasise are as follows: First, our primary challenge at this time is not so much that alternatives are absent. Far from it. Since 1999, various alternatives have been tried out and continue to be experimented. Even now, leading consociationalists see the current Nigerian presidentialism as a good case study in electoral reform in managing conflict in divided societies. The policies and politics of alternatives are, however, unevenly spread over time and space. This fact partly explains the variegated geometry of change which we are witnessing in the country.

The second point I would like to make is that for far too long, our political culture has perpetuated the myth that strong and charismatic leaders can bring about change single-handedly – rather than convert the formal authority derived from their electoral mandate into a process of democratic renewal. Based on my own direct involvement and practical experience, on the field, innovative social change can only occur with a leadership dedicated to motivating people to solve problems within their own communities, rather than reinforcing the over-lordship of the state over its citizens. The main challenge of political leadership in this context therefore is to reconnect democratic choices with people’s day-to-day experience and to extend democratic principles to everyday situations in citizens’ communities and constituencies.

Considering where we are today in Nigeria, it is my proposition that the next big challenge which history beckons on us all to respond to is how dispersed sites and actors of the alternatives can be meaningfully united and forged into a national movement of enduring change in which Nigerians across different geographies can recognise themselves.

What my colleagues and I did in Ekiti under my overall stewardship had its place and will continue to remain relevant. Similar efforts as we deployed in Ekiti have been played out and are still ongoing in various states of the federation. These efforts would need to be united as part of a broad leadership consensus for national rebirth. Doing so will require its own politics and a visionary type of leadership that is able to rise above faction and fraction to project a new national imagination.

I thank you all for your kind attention.

Dr. Kayode Fayemi, former governor of Ekiti State and Chairman of the Nigerian Governors Forum delivered this keynote address at the Conference on Redesigning Democracy held at the University of Oxford on Thursday 20 October, 2022.